David Cassidy … Some Questions Answered

Some 30 years have passed since I ghost-wrote David Cassidy’s autobiography, “C’Mon Get Happy.” The book continues to sell, and I continue to get questions from David’s fans. If I so much as mention him on Facebook—perhaps offering a toast to his memory on his birthday—people will message me with inquiries. I tried to answer some of the questions I got with a lengthy article that I wrote for this publication five years ago, “David Cassidy: Behind the Scenes.” But I still continue to get all sorts of questions.

By CHIP DEFFAA

Editor-at-Large

Some 30 years have passed since I ghost-wrote David Cassidy’s autobiography, “C’Mon Get Happy.” The book continues to sell, and I continue to get questions from David’s fans. If I so much as mention him on Facebook—perhaps offering a toast to his memory on his birthday—people will message me with inquiries. I tried to answer some of the questions I got with a lengthy article that I wrote for this publication five years ago, “David Cassidy: Behind the Scenes.”

But I still continue to get all sorts of questions. Not questions about his abundant talents and accomplishments—his fans are well aware of such things. And his enduringly popular recordings certainly speak for themselves. But fans will hit me with random questions about his life offstage such as these: “Is it true that David Cassidy died broke?” “Why did David exclude his daughter, Katie Cassidy, from his will? Why weren’t they closer?” “How did David feel about his son, Beau?

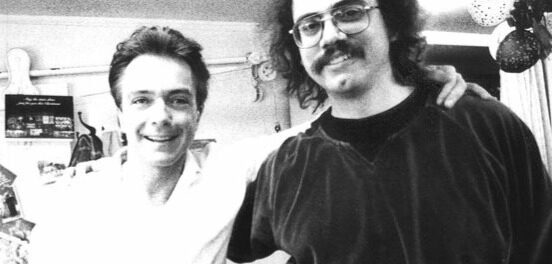

David Cassidy & Chip Deffaa

His wife Sue Shifrin?” “Did David hate his dad, Jack Cassidy? He expressed so much anger towards him in the book.” And “How do you think David will be remembered?” I’ll try to answer some of these questions, and others, today. This will be a long piece. I’ll do my best to thoughtfully convey what David told me. And while I have talked, over the years, to some other people referenced in this piece, I’m only trying to share here what David told me, how things looked from his perspective.

* * *

First, let me acknowledge that David certainly has some terrifically loyal fans who are doing everything they can to keep his memory alive. And I’m glad for that.

Camellia Hoare, Sian Harries and other devoted longtime fans have already arranged to have roses planted in David’s memory, along with a commemorative plaque, at the West Orange, New Jersey Holy Trinity Episcopal Church, where Cassidy was a soloist in the junior choir as a boy.

On July 30th, 2025, the township of West Orange, NJ, where David spent much of his boyhood, will honor him by co-naming the street on which he lived (“Elm Street”) “David Cassidy Way,” and by placing a historical marker on Colgate Field, where he played Little League as a boy. Cassidy will be celebrated in West Orange for two full days, in a gala event organized by fans Barb Collentine and Karen Ranieri. They’ve spent two years working to make this two-day event happen. (For more info on the upcoming events honoring David Cassidy, check the David Cassidy West Orange Historical Marker Facebook page, or send an email to: Davidcassidytributewalk@gmail.com.)

West Orange Mayor Susan McCartney has written, in support of the event: “Greetings, Fellow David Cassidy Fans…. These prestigious recognitions will forever memorialize David Cassidy’s dynamic legacy and his popular talent, which at one point in his career garnered a fan club that surpassed that of Elvis and the Beatles!”

Cassidy’s son, Beau, and daughter, Katie, are both expected to attend the ceremonies honoring their late father, and that makes me very happy. They’re scheduled to be there along with photographer Henry Diltz, writer Johnny Ray Miller, podcast-host Carol Kaplan, and others.

I can’t make it to those ceremonies, at months end, honoring David; I’ll be out of the area on those days. But I visited West Orange once again, this afternoon, as my own private way of remembering. (I had driven David out there from New York City 31 years ago; I revisited some of the same places today, Saturday, July 19, 2025.) I was surprised how emotional today’s visit was for me.

David was a wonderfully talented fellow, and always interesting to be with. At the peak of his commercial success, he was the highest paid solo concert artist in the world. But David had as much sadness in him as anyone I’ve ever known. He’d been hurt badly by Hollywood, and by various people whom he felt had used him, or had tried to take advantage of him, or exploit him. He took his anti-depressants. He used his best acting skills to smile for, and charm, his public as needed.

Standing by his boyhood home at 23 Elm Street, in West Orange, NJ today, and at the Little League field in nearby Colgate Park prompted lots of memories for me of talks that we had over the years, when he’d sometimes sound like a lost little boy; and my heart went out to him. That poor guy deserved better.

* * *

Well, I promised that I’d try to answer some of the questions fans have asked me. Let me give this a shot….

First. People ask: “Did David die broke? Was he able to leave much to his son?” That’s actually not quite as simple a question to answer as some might imagine.

For David Cassidy—in some ways—appears to be worth more, to be valued more in death than he was in the final years of his life.

The former pop idol—who died in 2017 at age 67 of kidney and liver failure related to his alcoholism—struggled financially in his last years. He certainly felt like he was going broke at that time—especially when his alcoholism and other problems brought him to a point where he could no longer work.

When he died, David Cassidy left a surprisingly modest estate–with an estimated value of $150,000, the press reported at the time of his death. But the real value of his estate has turned out to be greater than those initial press reports suggested. Let me give you some facts to consider.

In the past year, Olivier Chastan’s entertainment-rights-acquisition-firm, Iconoclast, has acquired Cassidy’s music-publishing catalog, recordings, and his name-image-and-likeness rights (known in the business as NIL rights), for a sum reportedly upwards of $10 million, according to “Music Business Worldwide.”

Beau Cassidy was quoted by “Music Business Worldwide” as commenting: “My father’s music and legacy continue to resonate with fans around the world, and I’m incredibly excited to partner with Iconoclast to keep his spirit alive. This collaboration will allow us to introduce his work to new audiences and ensure that his influence continues for years to come.”

David Cassidy’s former manager, Jeff Jampol, who helped put together the deal, noted, as “Music Business Worldwide” reported: “David Cassidy was not just an entertainer; he was a cultural icon whose contributions shaped the landscape of both television and music. Teaming with Iconoclast is the perfect way to honor his life’s work.”

The company Iconoclast, which was founded by Chastan in 2021, has also acquired the music assets of the late, legendary pop singer Tony Bennett, as well as those of The Band’s principal songwriter, Robbie Robertson. Iconoclast is acquiring the rights of commercially successful rap and reggae artists, as well. And the company that Chastan previously headed, Iconic Artists Group, made news when it acquired the catalog of the Beach Boys.

Chastan–a French musician-turned-entertainment-industry executive–has declined to say who is funding these major acquisitions. But his backers obviously have deep pockets. And Chastan has made it clear he is interested in acquiring all rights to well-known artists who’ve achieved great commercial success; he is not interested in discovering new talent.

He has also stated that, in the long run, he believes that the “name, image, and likeness rights” that he is acquiring may actually be the most valuable assets that he’s acquiring. He told “Creative Industry News” that “Name, image and likeness rights will be as important as music rights in the future.”

As virtual-reality and artificial-intelligence technologies continue to advance, owning all rights to iconic artists may well pay off in ways that are impossible and almost unimaginable today—conceivably including the production of new recordings, films, concerts, and so on, featuring legendary deceased stars.

But why has Chastan, the founder and CEO of Iconoclast, chosen to acquire all available rights to David Cassidy? Chastan told “Music Business Worldwide”: “David Cassidy’s contribution to pop culture far exceeds his teen idol image, and still resonates with fans and luminaries such as Quentin Tarantino who called Cassidy ‘one of the most underrated vocalists in the history of rock and roll.’ He was the first teenage superstar whose fanatical following overshadowed a true artist. He also wrote the playbook for everyone that followed from the Backstreet Boys to Harry Styles. Cassidy’s legacy, art and aesthetic are ripe for reintroduction into the cultural bloodstream.”

Chastan and his backers are confident enough in the future commercial value of David Cassidy and his work to be willing to reportedly gamble upwards of $10 million on their belief.

Cassidy’s fabulous career had far more ups and downs than most. But Chastan believes there’s much more to come in the David Cassidy story. I hope he’s right. And if he can do more to get that wonderful Cassidy voice out there again, I’m all for it. Time will tell.

* * *

I liked David. I was glad he picked me to ghost-write his autobiography, “C’Mon Get Happy.” He was smart, funny, and multi-talented. More talented—as a singer, songwriter, musician, and producer—than many people gave him credit for. And he had a wonderful knack for reinventing himself professionally. Long after many in the industry had written him off as a supposed “has-been,” he scored huge successes in Las Vegas, impressing the powers-that-be with his considerable skills as a producer, not just as a performer drawing record crowds to his shows.

David was also rather private. He did not open up to too many people. He’d been burned so badly in Hollywood in his youth that he became exquisitely sensitive to—and wary of—people he thought might be trying to use him, or exploit him, or take advantage of him in any way. And he kept his distance from most people. By choice, he lived in Florida, which he felt was about as far away from Hollywood as he could get; he wanted a home out of the spotlight, where he and his wife could raise their son.

Throughout his nearly 50-year career, I was happily surprised by the way he repeatedly managed to achieve new successes, making “comebacks” of sorts—on his own terms–after many had given up on him. I admired his resilience, his determination, and his focus in pursuit of his goals. I admired the way his goals evolved. Once he became a father, he told me many times, his primary goal was to be a good father. That meant far more to him than being the biggest possible celebrity.

It bothered David’s most devoted fans that he was not inducted into the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame. But that honestly did not bother him at all. He did not care anymore about such trappings of celebrity-status. He cared about being a person his son would remember fondly.

In the end, David could not overcome alcoholism; that’s certainly a tough disease to fight. (And he fought it for many years.) But he brought a lot of joy to an awful lot of fans in his lifetime. I’m glad that Iconoclast is willing to gamble such a sizable sum now on the future appeal of David Cassidy’s work. And I’m glad that David’s son, Beau, who meant the world to him, will be a beneficiary.

David Cassidy’s memoir, “C’Mon Get Happy,” continues to sell. (I continue to get royalty checks, which I certainly never anticipated when I began working on the book, three decades ago. The Kindle edition is available on Amazon.) I still get questions about David, his work, and his family from fans who’ve read that book, or an article that I’ve written, or perhaps have heard me talk a bit about him in a lecture. (And I even included David as a character in one of my plays, which he got a kick out of.) I can’t respond individually to fans who write me with questions. Instead, I’ll answer some of the questions people often ask me, in this article.

But first, a little background on David might be in order here. We told a lot about his life in his memoir, “C’Mon Get Happy.” But the original manuscript that we collaborated on (with him sharing tape-recorded recollections with me, which I turned into a book) was twice as long as the published book. That is to say, for every anecdote or observation that wound up in the published book, there was another anecdote or observation that he wanted to share, that he approved for publication, that Warner Books had to cut in order to keep the book to a manageable length. (There were also, of course, a number of off-the-record comments that I’ll simply take to my grave. This article consists of material he shared on the record.) Let me tell you a bit about the David Cassidy I knew.

* * *

David Cassidy made millions in the 1970s. He was the number-one teen idol. At his peak, he was the highest-paid solo concert artist in the world, playing bigger venues and pulling in greater box-office revenues than even Elvis Presley. He was a charismatic performer on stage, and could excite fans packing 60,000-seat stadiums to a frenzy.

From 1970-74—his peak years as a pop idol—he was living what fans might have imagined to be a dream life. He was enormously popular; images of him were on countess posters, beach towels, and lunch boxes. He starred on a hit TV show, “The Partridge Family”; his concerts, internationally, sold out quickly. You might ask: “Who would not want to be him? It sounds like he had it all.”

But he personally experienced those years—as he told me repeatedly—as years of non-stop stress. He was constantly working—television, recordings, concerts, and so on. And he felt like producers controlled every aspect of his life; they decided what his public image should be, and how he should fill his time; they picked the songs he should sing, and how the songs should be arranged. (For a while, they even electronically altered his voice, speeding up tapes to make his voice sound higher, lighter younger.)

There was no time in his life for reflection. Having a meaningful relationship with anyone was impossible; he had virtually no free time. Fans and groupies were always offering to service him sexually; his sex life consisted mostly of fleeting encounters with people he did not know, or did not know well. (And often, he added, people did not want to know well.) Such fleeting encounters, he stressed to me, provided him with some physical release—he had a strong, healthy sex drive–but they were, for the most part, emotionally unsatisfying, unfulfilling. However, there was virtually no time for him to really date anyone, or even to learn how to make a relationship work.

He was making tons of money—more money, he noted, than his father (Jack Cassidy), his mother (Evelyn Ward), or his step-mother (Shirley Jones) ever made. But there was no time to really enjoy it. Managers, agents, producers considered him a money-making machine. He felt he’d been sucked into a celebrity-making system that, ultimately, did him far more harm than good.

He also lived beyond his means. In the late 1970s, he partied too hard, invested unwisely, and paid little attention to where his wealth was going. (I remember him telling me, “In one year, I lost eight million dollars. Now, eight million dollars might not sound like a lot of money to you, Chip; but it was a lot of money to me.” I told him, “Eight million dollars is a lot of money to anybody.” And that was even more true back in the 1970s and ‘80s. Eight million dollars in 1975 would be the equivalent of about 45 million dollars today.)

In 1977, Cassidy married actress Kay Lenz; they divorced in 1983. In 1984, he married Meryl Tanz, but they knew pretty quickly, he told me, that their marriage was not going to work.

By 1986, the year that he and Meryl Tanz separated (they divorced in 1988), Cassidy was not just broke, he told me, he owed a fortune and had no idea how he could repay it. He and Tanz finally agreed to divorce. At this point, he told me, his career appeared to be over; he was getting no offers of work. And he had acquired a reputation in the industry for unreliability, due to substance-abuse issues.

By this point, he had less than $1,000 in the bank. He did not own a car. He had no home. He had few personal possessions—just those belongings he could carry with him when he left the house that he and Meryl Tanz had shared.

He crashed at the apartment of his longtime best-friend, Sam Hyman, and then at the apartment of Hyman’s sister–deeply depressed over the mess that he felt he’d made of his life. And trying to drown his troubles in drink (and in drugs) did not help.

His debts kept mounting. He had bank loan payments to make, and lawyers’ bills to pay. He did not feel he was in good enough shape, emotionally, to work, even if offers to work were coming in. And they were not coming in. The Hollywood movers-and-shakers who’d once treated him like a god were no longer even returning his phone calls. At the worst point, he told me, he figured that he was around $800,000 in debt (or about $2.4 million in debt, in terms of 2025 dollars). And he was despondent.

But after hitting rock bottom, he resolved to turn his life around. And to a considerable extent, in the years that followed, he managed to do just that. He spent countless hours in therapy, which he felt was of some value. But he told me he credited his ever-supportive girlfriend, composer/actress Sue Shifrin, whom he married in 1991, with making the most important difference in his life.

Shifrin, his third wife, brought much-needed stability into David Cassidy’s life. Their marriage—by far the longest-lasting, most significant meaningful relationship in David’s life—endured for 24 years.

And David wanted to be the best possible father to the son they had, Beau Cassidy (born in 1991). Fatherhood, David told me, gave him a new motivation to get his life together. His son’s welfare was important to him—more important to him than even his own welfare.

In the 1990s, David Cassidy worked really hard—with a kind of relentless, grim determination–to dig himself out of the financial hole he was in, to get his substance-abuse issues under control, and to rebuild his career. I told him I was very proud of him; his work ethic in that period was incredibly strong; he was focused, and seemed highly motivated–almost driven—to prove that he still had it.

I might also add, he definitely was not happy, although he masked that from the public. Offstage, when we talked, he could express to me despair. He told me he’d given up on expecting to ever find much happiness in life. He told me he’d “lost the capacity to experience joy.” (He believed that, due to abuse of alcohol and drugs, he’d burned out pleasure-receptacles in his brain. That’s exactly what he told me. He’d given up on experiencing the kind of joy he took for granted as a boy.) But he wanted to prove to himself that he could still succeed as a performer.

And—at least as important to him–he wanted to be a good father to his son. He wanted to be a far better father than his own father, the actor Jack Casidy, had ever been to him. Those were his primary goals, he told me repeatedly, his highest priorities.

* * *

When he asked me in 1994 if I’d be willing to ghost-write his autobiography, “C’mon Get Happy,” I initially told him no. But he managed to persuade me to do it. David could be very persuasive when he wanted to. And he put on a charm offensive, telling me how he really liked my writing in the New York Post, which he found “conversational” in style; how he felt that he and I connected well—which was the main thing; he trusted very few people–and how he really needed my help. He promised he’d answer honestly and candidly any questions I might have; no subjects would be off limits. And I’d have complete access to him—starting with his own phone number, so I could simply call him directly if I ever had any questions.

I finally told him I’d write the book because I liked him and thought it’d be an interesting project. But I stressed that I doubted the book would ever sell many copies. Friends in the industry had told me that David was widely considered a “has-been.” I told David not to get his hopes up for any commercial success with the book, that his time as a superstar had passed, that the young fans who’d idolized him in the 1970s had moved on.

When he read the manuscript of his life story that I wrote, based on my interviews with him (and others in his life), he told me he was sure the book would be a best-seller; that it would get him onto Oprah Winfrey’s TV show and many other TV and radio shows; and would be turned into a made-for-TV movie. I shook my head and told him I doubted any of those things would ever happen.

But boy–was I wrong! Every single thing he predicted would happen did in fact happen. The book, which sold tremendously well, played an important part in revitalizing his career. (And editor Karen Kelly did an amazing job of halving the manuscript’s length, while preserving the essence of his story. I’ve never worked with a better book editor.) I did some PR with David, too. He was great about doing every interview, for radio or TV or print, that people wanted.

David’s terrific success with both reviewers and the general public in the musical “Blood Bothers”—both on Broadway and in the lengthy national tour that followed the Broadway run—did not go unnoticed in the industry. Nor did his subsequent successful comeback concert appearances. He was rebuilding his reputation, day by day. I liked all of that.

To my great surprise, his 16th solo album, “David Cassidy, Then and Now” (2002), went platinum, he told me. (I never imagined he’d have an album on the charts again.) He was glad fans were buying new recordings he was making.

He was happy with the TV movie about his life, “The David Cassidy Story” (made in 2000). My own feelings were mixed. I liked the recordings David made for the film; he was in great voice, re-recording for the soundtrack his early hits in their original arrangements. But I thought that Andrew Kavovit, portraying David, was too weak and whiny throughout; he didn’t have the sass or verve, or wonderfully cocky self-confidence David could always project in public (even when he was actually feeling terrible). In scene after scene, Kavovit seemed to be playing a hapless victim—which wasn’t the essence of David at all.

And the script struck me as a highly sanitized, tamed-down, G-rated adaptation of our book, “C’mon Get Happy,” missing the abundant sex and the emotional extremes that gave the book its edge. I hope that someday a more honest film of David’s life, with more of the flavor of the book, could be made. (And Iconoclast—now owning David’s recordings, music-publishing rights, and name, image and likeness rights—would be well-positioned to get such a film made.)

In the 1990s and early 2000’s, David was making good money, rebuilding his wealth. But if I tried to compliment him on his financial successes, he’d say something like: “Chip, it doesn’t matter how much money I make. I’ll never be able to hold onto it; I can’t do that. I’ve been broke before and I’ll be broke again. I’m a screw-up, a fu*k-up.” David felt there was a self-defeating streak inside of him, just as there had been one inside of his father. He expressed this so strongly and repeatedly to me, I feared it might be a self-fulfilling prophecy.

He’d also tell me that he’d stopped drinking on doctors’ orders–that doctors had impressed upon him that he must not drink at all. (This was long before he first publicly acknowledged, in 2008, that he had a drinking problem.) But if we had dinner together, maybe he’d order some white wine. If I questioned why he was drinking—even a little—despite doctors’ orders that he abstain completely, he’d respond a bit too vigorously, too defensively, saying something like: “It’s just a glass of white wine. Who was ever harmed by one glass of white wine, Chip?” It was the same sort of rationalizing (“How can a little white wine hurt?”) that I’d heard before from other people I’d known who were alcoholics. To me, saying things like “How can a little white wine hurt?” was part of the disease of alcoholism.

If we were at some reception, where waiters were carrying around trays of drinks to give to people, he’d tell the waiters, “No, thank you; I don’t drink.” But later maybe he’d be taking sips from other people’s glasses, as if he needed “just a taste” of alcohol. He was certainly functioning well; he appeared to have everything under control. But his taking those little drinks, after doctors had told him he must not to drink at all, worried me.

David mentioned to me more than once that his father had a drinking problem, “but he was in denial about it.” And he added that his grandfather had also had a drinking problem, and he wondered aloud if something like that could get passed down, in the genes. It seemed to me, at moments like that, that on some level he knew—but didn’t want to admit he knew—that he might still have a drinking problem.

* * *

David scored major successes in Las Vegas, becoming one of the top attractions there, starring in shows that he personally produced. (I was impressed by his producing savvy. And he put together some very big shows. When mounted and starred in his “At the Copa” show, he had 77 employees working for him.) Financially, he was doing better than ever. But he was working so much that his wife and son, who hated Las Vegas, saw little of him. For about six months, during the Las Vegas years, David and his wife were separated; he was living as a single guy. As always, there seemed to be plenty of showgirls, fans, and groupies eager to provide him with some companionship. Some, he knew, even hoped or imagined that they might become his future wife, or permanent exclusive companion. But he wasn’t interested in them that way.

David wrestled with his options, finally deciding—in order to save his marriage to Sue Shifrin and to give his son a better upbringing—to abruptly move from Las Vegas to the much quieter Fort Lauderdale, Florida. He was making a major decision in his life.

He chose to cut back greatly on his workload, to become more involved in his son’s life, finding satisfaction in attending all of his son’s ball games, and even helping to coach his son’s ball team. His goal was the be the best possible father. And again, I found myself admiring him; he wanted so badly to be the kind of devoted father to Beau that he’d always—vainly–had wanted his own father to be to him. And he did the best he could, for as long as he could, until his alcoholism took its final toll.

* * *

In David’s final years, his arrests for driving under the influence made it all-too-apparent that he did indeed have a drinking problem. He went into a rehab program, but it was too little, too late. The drinking ultimately got the best of him; he had to give up performing. He could no longer remember lyrics to familiar songs, or perform well in concert.

In 2015, he filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. He’d gone broke once again, just as he had predicted to me. He even had to give up his beloved home. It was sold, at a bankruptcy auction.

* * *

When David died in 2017, I was tremendously saddened. I liked David. He had plenty of natural charisma. I’d seen, in earlier years, the magic he could create on stage. Seen the joy he could give to fans, even if he wasn’t feeling it himself. And I’d seen the sexual magnetism he had. I’d seen the way he could greet fans, whether at the stage door or at some random event. Some of the people were clearly interacting with him simply as regular, admiring fans, asking for an autograph and such; but some others (guys, as well as gals) would be trying to flirt a bit with him, or would be offering their phone numbers, or asking if they could get together to talk some more or have a meal or something. He was gracious with everybody; he took time to make small talk, if possible. He could make everyone feel that yes, they were important to him. And leave them feeling that maybe, just maybe, he’d give them a call some time. (And sometimes he did choose to call.)

Speaking with him one-on-one—without his fans around, just David letting his hair down with me—he could often voice sadness, regrets. He would ponder the fact that he no longer could experience the emotional highs, the elations, the joys that he had so often—and so easily—experienced as a boy. He had gone through so much stress in his years as a top pop idol (roughly 1970-75) and in the decade or so that followed, and he had indulged so heavily in drugs and liquor during the worst of those later years—he felt that his brain had been permanently affected. His capacity for feeling joy had been permanently muted. And he also felt that he’d been rendered, permanently, more vulnerable.

He learned to avoid, as much as possible, people who added stress or irritation or aggravation to his life. He trusted his instincts; if he had any sense that someone might be interested in using him or was toxic to him, he’d cut them out of his life. He said he did not have one minute—one moment—to waste on people who brought him down.

He learned to cherish the relatively few people who treated him with real kindness and love. Kindness meant a lot to him. David was extremely sensitive to mistreatment, slights, and disrespect. And he knew instinctively who was truly in his corner.

He found satisfaction where he could—in his family (meaning, his wife and his son), and in his work, and a few close friends. And oh! He sure loved horses–as much as anyone ever could. And he sure enjoyed spending time with them.

He often spoke bitterly of what Hollywood had done to him. It had robbed him of his youth, he told me, and of any sense of control over his life. And whatever it had given him in return—fame, money, easy access to casual sex with fans, groupies, and the like—those things had not brought him satisfaction. He stressed to me as strongly as he could that he would not want any child of his involved in Hollywood. What any child of his might choose to do as an adult would be, of course, that individual’s choice to make. But he would not want any kid of his to give up even one moment of youth for the empty promise of fame that show business might offer.

David did not believe that being a celebrity was a good goal for any young person to have. The whole concept of being “a celebrity” was, he felt, pretty much bull.

David could get quite intense, discussing such things as Hollywood, fame, and America’s incredibly foolish—as he saw it–fascination with celebrities.

* * *

When I remember David, I like to remember the times when he seemed, in his own quiet way, to be gently contented with life, when he was having a good day and was grateful for it. One very good day was the day in 1994 that I drove him out to West Orange, New Jersey. We made that trek for two reasons.

First, we thought that just driving around his home town—going wherever he wanted to go—might stir up fresh memories for the book we were collaborating on (“C’mon Get Happy”). And boy—did it ever! Many more memories than either of us anticipated. I had the tape recorder going the whole time. The visit prompted lots of good memories for him. A few not-so-good memories as well.

But he stressed he’d been much happier, overall, in sleepy little West Orange than in Hollywood. When we visited his boyhood home on Elm Street, he wanted to go inside but no one was at home. However, just being there prompted lots of memories, and he could describe to me the whole little house as he remembered it so well, from the cold, dark, unfinished basement to his own bedroom upstairs, where he’d put pictures of his boyhood hero, Mickey Mantle, up on the wall. We went around back; he liked that there was still the clothesline his family had used when he was a boy; they were too poor to afford a clothes dryer.

We also went to West Orange that day because he was being honored by the high school. He’d been invited to speak to the students in a special assembly. That was a very big deal for him. And even his mom, Evelyn Ward, came out for the occasion. I sat with her as David spoke; I enjoyed her company a lot.

David loved the kids and gave unstintingly of himself that day. I took lots of pictures, far more than we could ever use—I was just glad to see David having such a great day. He did not want to go home. He stayed after the assembly, talking individually with every kid who wanted to talk with him. He exchanged contact info with some, and even stayed in touch with some in subsequent years. That was, for him, he noted with satisfaction, a VERY good day.

We took a leisurely route back to New York City. At one point, as we were on Route Three, David sat upright in the seat of my big old Lincoln Town Car, as if startled. He said we were at the exact spot where his father, Jack Cassidy, had told him, when David was a kid, that he and David’s mother had gotten divorced. And being at that spot prompted some vivid memories of Jack Cassidy.

It seemed to me like whenever David and I got together, we ultimately wound up talking about Jack; David’s father, who’d so often disappointed him, always loomed large in David’s thoughts. But this time, for a little bit, it was almost as if the fellow sitting next to me in my car was no longer the grown-up, world-famous David Cassidy—my complicated friend, who was the same age as I was–but just a little boy, shaken by the idea that his father was abandoning him by divorcing his mother. And we talked through that for a bit. And he finally said he was OK; he said he “hadn’t exactly forgiven Jack”—but he’d made his peace with Jack. And David complimented my big old Lincoln Town Car, as he’d done before, saying: “Jack would have loved this car, Chip…. I mean, it’s just so Jack.”

David and his father did not speak to one another at all in the final nine months of Jack’s life. David told me that was one strong regret he had in life, that he’d let things get to that “We’re-not-speaking” point. David told me: “I really regret not saying, ‘You know, Dad, I really love you, and I’m sorry.”

His father hurt him many times. The last time occurred when Jack Cassidy’s will was read. Jack left absolutely nothing to Jack, not even a token keepsake. Jack’s estate—the value of which was estimated at $100,000 upon his passing in 1976—was to be divided equally among Jack’s sons Shun, Patrick, and Ryan Cassidy, and Jack’s nephews. David was stung. When some of Jack’s belongings were auctioned off, David paid $1,000 for Jack’s pocket watch, just to have something of his.

Fans often ask me: “Did David hate his father? In ‘C’Mon Get Happy,’ he said so many negative things about his father’s treatment of him.”

No, David insisted to me that he did not hate his father, although he often got angry—infuriated—when recalling him. David had been hurt by many things his father had said and done; and yes, talking about that was a big part of his motivation for writing the book. His father had failed him in many ways, in his boyhood. His father had made—and broken—so many promises to him. And David felt he’d been scarred by all of that.

David told me repeatedly how badly he wanted to be a better father to his son than his father had been to him. He could—and did—often vent about his father’s shortcomings as a father.

But David also insisted to me, just as fiercely, that he loved his father, that he was proud to be Jack Cassidy’s son; that everyone in the Cassidy family knew that he, David, was much more like his father than any of his father’s other sons.

Yes, his father could be vain and self-centered, David would say—and then he’d surprise me by adding, “That’s where I got it from. And don’t you think vain people are interesting?” Yes, David acknowledged, his father sometimes drank way too much—as had HIS father before him. And David acknowledged that he thought he’d inherited that propensity, as well. But, he’d add, no one could resist Jack Cassidy’s charm. And David was glad he’d inherited a bit of that. David insisted that his father was the greatest musical-theater performer he’d ever seen on stage.

His father often infuriated him, David acknowledged. But then he’d tell me, “Let’s get a meal at Frankie and Johnny’s Steakhouse”—simply because it had been his father’s favorite restaurant, and he felt a kind of connection with his father just sitting there. He certainly wasn’t going there for their famous steaks–David didn’t even eat beef! He was simply going to Frankie and Johnny’s because he could sort of feel his father’s presence there. And that was comforting. (Today I will drop in to Frankie and Johnny’s Steakhouse—even though it’s moved to a different location, a couple of streets away from its original location, in the theater district of New York—because it still reminds me of David.)

David could voice tremendous ambivalence towards his father. He was painfully aware of his father’s shortcomings as a parent. But David was also mature enough—insightful enough—to acknowledge that in the many arguments he’d had with his father about how he should live his life, his father was usually right in the advice he gave, although it took David years to realize that.

In his own way–David eventually came to believe–Jack Cassidy had tried to protect David from the damage that Jack could see that Hollywood was doing to him. But David could not hear it at the time. When David became, in the early 1970s, the number-one teen idol—suddenly rich, famous, popular—Jack tried to warn him that being a celebrity could be a trap. That there were much better goals to have in life than merely becoming popular or famous.

Jack told David that people who chased after celebrities–and were blinded by all of the manufactured glamor–were fools; that the whole teen-idol phenomenon was a house of cards that would eventually, suddenly, fall down. And leave David with nothing. David did not want to hear any of that.

Jack told David that he’d feel better about himself doing a good Broadway show, for less money, than living this vapid “teen idol” kind of a life. He’d ultimately find it unfulfilling. David told his father, “You’re just jealous of my popularity.”

Looking back, as we worked on the book, David told me that maybe his father WAS somewhat jealous of his popularity back then. But David could also see that, on the main points, his father was right. His father saw the dangers in the path David was on in he early 1970s, well before David saw those dangers. His father told him repeatedly that he’d find more satisfaction in life if he simply aimed to do the very best work that he was capable of, rather than aiming to be as big a celebrity as possible. Jack Cassidy—as imperfect as he was—was trying to share with David some hard-earned insights. But it took David many years, he told me, to fully understand what his father was trying to tell him.

I was disappointed in the made-for-TV movie, “The David Cassidy Story,” that came out of our book. But David liked that the movie got one key thing right—it showed both the conflicts that David had with his father and the fact that, in the end, David found a way to make peace with his father, and find satisfaction in his present life with his wife and son. The movie had a happy ending that David felt—or hoped, anyway–reflected the essence of his life at the time the movie was made.

And I kind of like the fact that the very last recordings David made were of songs he’d learned from—and associated with—his late father. David’s love for his father, in the end, outweighed the understandable anger towards him that he’d so often expressed.

* * *

When David died, as the press reported at the time, he left virtually his entire estate–with an estimated value of $150,000–to his son Beau. David also left music memorabilia to his three half-brothers, Shaun, Ryan, and Patrick Cassidy.

David chose not to leave anything at all to his estranged daughter Katie. As “People” magazine reported (December 6, 2017), he wrote in his last will and testament: “It is my specific intent not to provide any benefits hereunder to Katherine Evelyn Cassidy.” His will specifically stated that while he acknowledged that he had two children — Beau and Katie — any references to his “child” in the will were intended to refer only to Beau and NOT to Katie.

Regarding their estrangement, “People” magazine quoted David as saying of Katie, earlier in his final year (February 17, 2017): “I’ve never had a relationship with her. I wasn’t her father. I was her biological father, but I didn’t raise her. She has a completely different life.” He was proud of her accomplishments as an actress, he stressed. He always wished her well. But for much of her life, he had had limited contact with her.

The New York Post’s Page Six quoted Katie as saying: “I didn’t meet my father until I was in the fourth grade. The world doesn’t know that. Not because I’m hiding it, it just hasn’t been discussed.”

When the press reported that David had left Katie out his will, fans of David Cassidy began writing me, messaging me about that, asking why David and his daughter had not been closer. Why were they apparently estranged for so many years?

Here’s the way David told me he saw the situation, going back to the very beginning….

* * *

For David, 1986—the year that Katie was born—was the worst year he’d ever known, the year that he felt he hit rock bottom. It was clear to him that his marriage to Meryl Tanz (whom he divorced in 1988) was a failure; and he questioned whether he could make any relationship work.

He was not just broke, he was more deeply in debt than he’d ever been, owing something like $800,000 (the equivalent of about $2.4 million today). His use of alcohol and drugs was out of control.

He could not find work. In 1986, the consensus in the industry was that he was washed up; he was through. That year, he told me, he could not shake obsessive thoughts that he was a failure and a f*ck-up, and would always be one. He was not looking for any kind of a relationship. He was in very dark place. He was suicidal, he told me.

And then one day he read, on the New York Post’s notorious—and highly popular—“Page Six” that he was being hit with a paternity suit. A 34-year-old woman in California, whom he’d previously thought of as an old acquaintance or friend, was saying that he was the father of her child (Katie). And the woman now had one of the world’s most prominent celebrity lawyers representing her. This high-powered celebrity lawyer had famously won large sums of money for his clients in “palimony” suits against performers. David wondered: Did the woman and her lawyer imagine that there were large sums of money to be squeezed out of David Cassidy? Was the woman after his money? He was actually dead broke, although he was sure that she didn’t realize it. (He was world-famous, a household name; but he had kept his problems out of the public eye, and she wouldn’t have known of all of his ups and downs.) David did not see how he could even afford a decent lawyer–much less a lawyer with the clout that her high-profile lawyer had.

He felt publicly humiliated—embarrassed–by the story in the New York Post, which he knew other papers would quickly pick up. He felt like the woman had publicly declared war on him. He wished she’d worked things out with him privately, discreetly. Any warm feelings he might have once had for her as a casual friend from his past, whom he’d seen from time to time, were now permanently gone.

David told me—repeatedly, and in the strongest, clearest terms—that he had no recollection of ever having had sexual intercourse with that woman. That he’d never thought of her as someone he’d ever want to have a meaningful sexual relationship with. That they had not been having an affair, he said. He’d thought of her a kind of old friend or acquaintance. Over the years, their paths had crossed from time to time. But he’d never been in love with her, and he’d certainly never wanted to have a child with her.

When the paternity test established that David was, indeed, the baby’s biological father, he accepted that reality; but still, he had no recollection of ever having slept with the baby’s mother; he certainly felt no bond with her. He figured that whatever had happened between them, he must have been drinking so heavily that he’d had a blackout. In any event, he told me, he had no memory of ever having sexual intercourse with her, or of ever wanting any kind of meaningful ongoing relationship with her. He wondered if she had wanted to have a child with him.

He agreed that he would make whatever child-support payments he was legally obligated to make (And he did so, he told me, even if he sometimes had to borrow money to make the payments.) But he had no intention of doing more than that. Baby Katie, he figured, would never miss a biological father whom she did not know.

David, in the end, decided he would let Katie’s mother and step-father raise her. But he did not care for the woman anymore, or desire to have any more contact with her than was necessary. He would steer clear, as much as possible, of Katie’s mother. And that was why something like 10 years passed before David began to gradually get to know his daughter.

He and the mother had first met, by chance, back in 1970 when he was doing “The Partridge Family.” He was then 19, she was 17; they hung out for a bit. He thought she was cute–he saw her as something of a starstruck farm girl, who liked the idea of being around celebrities. That was his first impression, anyway. And she was doing some modeling back then, and even a little bit of acting, as were so many of the girls he seemed to meet in Hollywood.

But she bought into the supposed glamor of Hollywood, he felt, in a way that he did not. He’d been around far too many celebrities to still have any stars in his eyes.

David told me it soon became clear to him that she wanted more from him than he could possibly give. She wanted him to be her boyfriend, for them to have an exclusive relationship.

He thought that idea was preposterous. She barely knew him. She knew that he was a rapidly rising star, of course. Everyone knew that; his face was turning up on magazine covers, on beach blankets, on school lunchboxes. His recordings were all over the radio. His signature song, “I Think I Love You”—the megahit that would forever be indelibly associated with him—was actually released even before “The Partridge Family” began to air.

She told him, he said, that she had no real interest herself in his “Partridge Family” TV show. She was not buying his records or buying tickets to his concerts. His music didn’t really appeal to her; he got the impression that she thought it was kids’ stuff, beneath her. She suggested that her own musical tastes were a little more grown-up than that. (That was David’s impression, anyway, he told me.)

And yet, she told him that she had fallen for him, and she thought they’d make a great couple. She thought she loved him.

He didn’t have those kinds of feelings for her. He didn’t even feel that they had much in common. Their values were different.

And it wasn’t just that. He was well aware he was becoming a hugely popular pop star. He had the highest “Q” rating (measuring likeability) of anyone on television. Fans and groupies were coming to his home, offering themselves sexually. (He was happy to oblige.) It felt like everyone seemed to want him. But his career was exploding so rapidly, he barely had the time or interest to think about ongoing relationships. And if he could find the time, there were gals he was much more strongly attracted to than this girl. (Meredith Baxter, for instance, really appealed to him, he said.) In addition, he didn’t feel that this girl was actually attracted to him as person so much as she was attracted to him as a celebrity. There were plenty of gals in Hollywood, he knew, whose dream was to become involved with a celebrity. And he certainly was “it” right now–the biggest rising celebrity. David hoped to find a girl eventually, who would like him for himself. This starstruck girl—who barely knew him and didn’t have seem to have much interest in the singing and acting he was doing–was certainly not the one for him. That was his perspective, anyway.

He told her that he liked her, but was really getting too busy to hang out much with her anymore. He figured, he told me, that she’d probably find another celebrity to connect with. And within a year or so, she was one of Elvis Presley’s girls. David told me that he ran into her at one of Presley’s concerts; she was watching the concert, as Elvis’s guest, from the wings. Presley always expected the girls he was seeing to watch his performances.

Of course, David knew, there really wasn’t much of a future with Elvis for any of the girls Elvis saw; Elvis was married, and the young girls around him seemed to come and go. But there were always new girls who liked being associated—even if just for a while—with “the King.” Elvis was famously generous to the girls around him, giving them clothes and jewelry, and such. And he welcomed their companionship.

David, I might add, liked Elvis and respected his talent enormously. He was glad that they became friends. As an artist, David looked up to Elvis. But it also saddened David, he told me, to see how Elvis—by then in his mid ‘30s–had damaged himself, personally and professionally, via his drug abuse. And he hoped he would not wind up like that.

* * *

David’s own life hit rock bottom, to his way of thinking, in 1986.

And then, gradually, it began to turn around. David began to rebuild his life, one step at a time.

He gave all credit to Sue Shifrin. For David, the most important event of 1986, he told me, was falling in love with Sue Shifrin. She reached out to him; they had dinner together. He knew at once, he told me–right from that dinner in 1986–that he wanted to have a life with her. As he put it: “I took her out to dinner, and since that night, we’ve been together ever since.” They didn’t formally tie the knot until five years after that dinner; but they were a committed couple—married in everything but name—for years before they wed.

As David told me: “Connecting with Sue really began to shift my life from the dark side back into the light. Just being around her—she was so positive, so supportive, so caring, so loving. Her whole attitude was so ‘I don’t care that you’re drunk, David, I don’t care that you’re a mess, and have no money.’ When someone embraces you at your lowest point, it really means something. It carries a lot of weight with me.”

He’d actually first met singer/songwriter Sue Shifrin back in the summer of 1973, while in England for a concert tour They’d hit it off right away—there was a strong attraction from the start. And he even blew off an invitation to meet the Queen of England, in order to have more time with Sue.

But that was during the breathless madness of David’s teen-idol days, when he was constantly on the move and barely had time to think, much less have a serious, ongoing relationship with anyone.

He enjoyed the brief time he got to spend with Sue Shifrin in the summer of 1973; but then, he told me, he had to get back on the plane and fly to the next stop on his tour, or whatever; and eventually return to the U.S. to do another season of “The Partridge Family,” and make more recordings, and on and on…. In the early 1970s, David had almost no free time. He was working nonstop back then, and one day blurred into the next. He liked Sue Shifrin from the moment he met her. But in 1973, he said, his life was so hectic that he had no time for relationships with anybody.

But now, in 1986, he wanted a real relationship with Sue. They fell deeply in love. And David liked the fact that they had so much in common. (He’d certainly never felt that way with Katie’s mother.) David and Sue were both creative artists—singer/songwriters with similar musical tastes. When David first met her in 1973, they were both signed to the same record label.

Sue really liked David’s singing and his songwriting, which meant a lot to him, too. He felt validated. She cared about his work, and was forever encouraging him to get back to it, to put his talents to good use. (He didn’t like the way Katie’s mother had shown so little interest in, or appreciation of, his work as a singer/songwriter.) They were both idealists. David could envision them both contributing their talents to charitable causes they believed in. Politically, David was always an outspoken liberal. (Katie’s mother’s political views were the opposite of his, he felt.) It was nice to be with someone he felt so “in synch” with.

In so many ways, at the time when David and Sue reconnected in 1986, David felt that he was “a mess.” He felt he’d made a mess of his whole life. And despite all of that, Sue had great belief in him as a person. That meant so much to him, he said.

David told me: “With Sue’s support, I made the decision to go into analysis at that time when emotionally, professionally and personally I had pretty much bottomed out. I found my analyst through Sue, who had benefitted greatly from analysis herself. Even though analysis is painful, it’s not anywhere as near as painful as living in the kind of misery I was experiencing. I just couldn’t stand it any longer….. I needed to fix myself. What were my choices? I could either walk around and get drunk and be angry and bitter, or I could say, ‘As long as I’m here, I want to feel good…’ My hope was that, through analysis, I could sort of rebuild my life. I didn’t hold out any hopes for my professional career, which seemed to all intents and purposes dead.”

But David wanted to change as person, to feel more “whole” (as he put it), to find more satisfaction in life. And Sue believed he could change. David took analysis seriously— three sessions a week with his psychoanalyst, for the next three and a half years. And his life changed in so many positive ways.

He gave up smoking cigarettes and cigars. He gave up drinking and using drugs. He gave up eating beef. He felt lighter, clearer, more focused, he told me. He and Sue wrote songs together, performing some for charity events. He went out on tour one summer with his own band, gaining some good publicity if few financial rewards. After expenses were paid, three months of touring netted him less than $1000 in profits, he said. He did much better financially, touring as the opening act for the Beach Boys.

He had his first American top-40 hit in years with his 1990 single “Lyin’ to Myself,” from his album “David Cassidy,” which was followed, in 1992 by an album “Didn’t You Used to Be” (which he felt was overproduced). And then the simpler “Old Trick, New Dog” album, which he liked more. He found work in motion pictures and television.

He wrote a theme song for “The John Laroquette Show,” which he submitted to the producers under pseudonym so it would be judged strictly on its merits, without being associated with the name of David Cassidy. He was happily surprised when his song was chosen and became that hit sitcom’s theme.

* * *

David was delighted when Sue gave birth to their son, Beau, in 1991. He felt that was the biggest, best gift Sue could have given him. He doted on their son. Having Beau, he told me repeatedly, changed him for the better, in ways that he never could have imagined or anticipated. It delighted him to realize he could be a good father. (David told me candidly that he’d been so self-centered, he had often doubted that he could ever be a good father. Neither he nor Sue—who was 41 and had been told that, for various reasons, she could never have a child—had sought to have a baby. Her pregnancy came as a surprise to both of them.)

It delighted David to put his son’s well-being ahead of his own. Producer/director Hal Prince invited David to take over the leading role in “Phantom of the Opera” on Broadway. David appreciated greatly that vote of confidence in him—but said the timing wasn’t quite right yet for him to make his return to Broadway. (He’d first appeared on Broadway in “The Fig Leaves are Falling” when he was just 18.) He wanted to take some months off now and just be a stay-at-home Dad with his son.

So many positive things were happening at once. All of this felt new and wonderful to him. He began to feel more optimistic about life, he told me. His wife liked the energy he was projecting, he said. She liked seeing him smile.

David also gained greater confidence in trusting his gut when he felt a need to steer clear of people whom he considered toxic for him–people who aggravated him, people who contacted him if they wanted something from him but had no kindness or love to offer him. People who were disrespectful of his own concerns.

David found success doing theater, in London (“Time”) and in New York (“Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamboat”). Fans and reviewers were rediscovering him. He was on a roll, once again. And for some 20 years following his re-connection with Sue Shifrin in 1986, he felt his career was doing rather well once again.

I remember him calling me several years after the release of the book we’d collaborated on, “C’Mon Get Happy.” He was still pretty much working nonstop, he told me; but it was all work that he WANTED to do, so he felt good about that. He still had his battles to fight with depression and anxiety, which he figured he’d always have to fight. (“Thank God for Paxil,” he quipped, referring to the prescription antidepressant /anti-anxiety medication.) But he sounded, on that day’s phone call, as genuinely happy as I’d ever heard him. I like to remember him that way, finding so much satisfaction in his work and in his life.

He was so pleased with the way the recordings were going for the new album he was working on. He didn’t care if the album sold 10 copies or a million, he said; he was happy because he was making exactly the kind of album he wanted to be making. He liked being able to express who he was. He was spending a lot of hours in the studio; but it was by his choice. He’d often felt frustrated making his early albums, he said, because there were always producers telling him what to do, running his life. And he’d never been good with authority figures. Or with letting others make decisions for him. But now, when he was nearly 50 years old, David felt he was finally, fully in charge of his life. That mattered to him more than how the album might do commercially. (And the album, as it turned out, sold pretty well, which was the icing on the cake. He was always grateful for the loyalty of fans, and amazed at times at how well recordings of his did in Europe and Australia.)

I mentioned to him that I was reading a new book about Elvis Presley and suggested he might like it. He didn’t have the time or interest to read a book about Elvis, he said. He’d known Elvis; that was enough. And he felt sorry about the way Elvis’s life had ended, with Elvis losing his battle with longtime substance-abuse issues. He identified with Elvis in some ways.

People had often compared him to Elvis, he noted. Saying that he was the biggest American pop idol since Elvis. But Elvis had wanted it, and had enjoyed it. David supposed there were plenty of people who dreamed of being a pop idol. But he’d never wanted to be one, he said. Not for a minute. And if he had his life to live over, he’d have picked a different path.

* * *

Katie’s mother, David told me, wanted more child-support money from him once it was apparent that he was making more money. He said he would meet his legal obligations; she’d get the level of child support that she sought. But other than that, he wanted to steer clear of that woman as much as possible. And he kept his distance; he trusted his instincts. He felt he knew what was best for him.

For David, his world—the unit he cared most about these day—consisted of Sue, Beau, and himself.

Of course, David said, he also wanted young Katie to thrive, even if he did not see much of her. He followed her growth and progress as best he could from a distance. David’s mother, Evelyn—who was Katie’s grandmother and enjoyed staying in touch with Katie and giving her a grandmother’s love—helped to keep David informed. David’s mother was Katie’s link to the Cassidy side of the family, David felt.

David hoped that when Katie was an adult–living on her own, not with her mother and step-father–he could have a closer, more supportive relationship with her. He looked forward to that time.

But in the meantime, of course, years were passing by.

* * *

Katie liked to sing and act and play piano, among assorted other interests. She appeared in school plays. And as Katie grew older, David said, Katie’s mother expressed hopes that Katie could become, just as David had been, a teenage superstar pop singer. The mother hoped that David would get behind such a goal for Katie, help Katie, at age 15, attain the kind of professional success that David had had in his youth. Maybe, the mother suggested, Katie could be the next Britney Spear.

David thought the whole idea was absolutely crazy. Katie was a good student; he hoped she’d go to a good college. He noted—as he so clearly put it–that he “couldn’t support her [Katie] becoming a pop diva. I would not support that for any young person, let alone my own child. I wouldn’t advise any parent to put their child in a situation where they’re going to lose their teenage years. It’s an unhealthy environment to be in.”

David believed strongly that kids should have chances to be kids, without having to deal with the demands and pressures of professional show business. His son Beau, he noted, enjoyed singing and acting. If Beau wanted to perform in shows at school or at summer camp, entertaining his peers and their parents, David thought that was great. (And David sent Beau to the best theater-oriented summer camp he could find–Stage Door Manor in upstate New York–where Beau shined.) But David didn’t want Beau, as a youth, performing professionally, or even thinking about becoming some kind of teenage celebrity.

David hated the thought of Katie heading down that path. He understood the potential dangers all too well. He knew how greatly—and permanently–he’d been harmed. He hated seeing Katie’s mother pushing the idea of her daughter becoming a celebrity. He’d seen plenty of stage parents who sought to live vicariously through their kids’ successes as performers. And he believed that wasn’t always good for the kids involved. He believed that too many people were fascinated by the idea of being a celebrity. A better goal for any young person, he believed would be to become as good as possible at the work you wanted to do. And be a good person.

David was appalled when Katie, at the age of 15, was signed to a recording contract. David believed that her mother–who had to approve of any such deals since Katie was a minor–was pushing Katie in the wrong direction. He had too many bad memories of his own experiences in Hollywood.

One local Southern California newspaper, “The Acorn” (June 13, 2002), reported Katie’s signing this way: “Katie Cassidy-Benedon, a freshman at Calabasas (CA) High School, has been signed by Artemis records, the largest independent record label in the U.S., for a five-album contract deal. Her first single, ‘I Think I Love You,’ is a new rendition of her father David Cassidy’s 1970 hit and features not only an updated arrangement but a rap and dance version as well…. This summer, Katie will tour as an opening act on several pop summer concerts.”

Let’s unpack that paragraph. First, Katie’s name at that time was, the newspaper reported, “Katie Cassidy-Benedon” (combining the last names of her biological father and her stepfather). But for professional purposes, she would be known henceforth simply as “Katie Cassidy”—because the intent was to market her as David Cassidy’s daughter; the Cassidy connection was the prime selling point. Had she been an unknown, whose last name was not Cassidy, singing songs of her own, David Cassidy believed, she would never have been offered that record deal at age 15; she had not made any kind of name for herself as a singer to warrant such an offer. She had not paid her dues.

And to emphasize as much as possible her connection to David Cassidy, her first single was a remake of David Cassidy’s best-known number, “I Think I Love You.”

David Cassidy—who was acutely sensitive to when people were trying to exploit him—hated what was now happening. He felt he was being used; people were trading on his name and fame, against his wishes. And he hated feeling used.

He didn’t blame Katie, he stressed; he blamed the woman he felt was pushing Katie in this direction. He felt disrespected that someone would choose to have Katie record his signature song to get ahead, against his wishes. The people managing Katie were making the most of the Cassidy name, David felt–using his name to open doors for her, at age 15, in the industry.

And David didn’t like the overproduced new recording of “I Think I Love You.” He felt like that sweet, simple pop song belonged to him–that catchy, innocent song that fans still expected him to sing at every show. And the people handling Katie were working so hard, it seemed to him, to try to make her rendition a hit. She even wound up singing “I Think I Love You” in a made-for-TV movie, “Bubblegum Babylon” (2002).

Katie’s name was now turning up in the press, too, here and here. She was reported as dating the teen pop star Jesse McCartney, and she appeared in a McCartney music video as his love interest. Young Katie could be seen in a music video of Eminem, as well. She was being promoted—heavily–as a rising celebrity. She appeared on the Nickelodeon Kids’ Choice Awards, the Teen Choice Awards, and the MTV Video Music Awards.

David, who understood better than anyone how the Hollywood publicity machine worked, hated seeing his daughter getting pulled into that all of that kind of celebrity-making machinery. He believed, with every fiber of his being, that he’d been permanently damaged by his experiences in Hollywood in his youth, by all of the celebrity-making whoop-dee-doo he’d been through; he didn’t wish that kind of stress-inducing “success” on anyone, much less on any child of his.

And David hated the fact that every time his name was now mentioned in connection with Katie’s, it might appear to the public as if he approved of everything that was happening. He did not.

David was invited to Katie’s high school graduation; he ultimately sent word that he expected to be out of the country at the time, on vacation with Sue and Beau. He was asked if he could fly back from vacation to attend the graduation. But David felt it best, he told me, if he spent the time with his wife and son, and Katie spent the time with her mother, stepfather, and family.

* * *

Katie’s recording career, as it turned out, never really caught fire. Becoming a teen pop singing star just wasn’t in the cards for her, no matter how much she and her mother might have once wanted that goal. David’s extraordinary success as a singer (20 million albums sold) could not easily be replicated; he had a unique voice, a great deal of charisma, and a rare gift for connecting with live audiences. He could play huge venues and still convey intimacy, still make fans feel that he was singing just for them. All of the promotion in the world could not make Katie Cassidy a recording star. The public has the final say.

But if Katie never became a teen singing star, the heavy promotion of her did at least make her name familiar to the public. And that helped opened doors for her as an actress. Katie made acting, not singing, her top priority. And she found a niche for herself.

David thought things had worked out for the best. He noted in “Could it Be Forever” (Headline Publishing Group, 2007) : “Katie now understands, at the age of 19, that I couldn’t support her wanting to become the next Britney Spears when she was 15. She’s glad it didn’t really happen for her then. She’s discovered that she is a very good actress and is working every day to become better at her craft. She doesn’t want to become famous because of me—she was driven towards that by another influence in her life….”

And David did not believe that becoming a celebrity for the sake of being a celebrity was a good goal for any young person to pursue. Even if he’d had a hard time explaining his views to his daughter. He reflected: “My advice was falling on deaf ears for a while, but fortunately Katie’s grown up and matured and she gets it now…. I’m very proud of her…. I supported her until she was 19 and now, she wants to be self-sufficient. She doesn’t want Daddy to take care of her. She wants to make it her own way, and that shows character.”

He noted: “In the past year or two, Katie and I have formed a deep, caring, loving, supportive relationship…. She’s doing what she loves to do. Which is acting…. She’s realizing her dream. She is working hard at developing her craft. She realizes that doing what you love and being good at it and working at it is far more important than having a bit of fame. I have preached that to her for a number of years. She does not pursue the fame or the money as much as she pursues the love of the work…. Fame for the sake of fame is emptiness. It’s just window-dressing. It’s just fluff.”

In an interview with “People” magazine (December 2, 2017), Katie summed up the advice that her father had given her over the years with these words: “’Do not work for money; do not work for fame,’ he said. ‘Work for the work. And if you get a great role and they offer you nothing, take it.’ That’s all he’s said, and I’ve taken the advice.”

The advice that David was trying so hard to impress upon Katie was actually the same advice his father had tried so hard to impress upon him when he was younger.

David also noted in “Could it Be Forever” (2007): “I hope that Katie is able to enjoy some of the rewards that I have been able to reap. But the important things are to be able to wake up in the morning and feel good about yourself, feel good about your work, try every day to be better at what you do and be a better person.” Not a bad philosophy to live by.

Once Katie reached adulthood and was living in a place of her own—no longer with her mother and stepfather–David tried to make up for lost time in getting to know her well. He hoped they could have a close relationship. He hoped they could be great friends. And for a while anyway, things seemed to be working out. As Katie told “People” magazine: “My biological father and I had a really good relationship at one point. He was one of my close friends and gave me wonderful advice.”

* * *

But establishing and maintaining a close relationship after many years of having had little or no relationship was not easy. Perhaps too much time had passed. Life seemed to be pulling them in different directions. And, David said, they pretty much wound up going their own separate ways, living separate lives with little contact.

Katie’s career as an actress really took off, and there always seemed to be some sort of work for her (often in horror projects). Among her noteworthy film and TV credits since 2005—far too numerous to list in full here: “When a Stranger Calls,” “Click,” “Black Christmas,” “Supernatural,” “Harper’s Island,” “Melrose Place,” “A Nightmare on Elm Street,” “Gossip Girl,” “Vixen.” She appeared on 152 episodes of the popular superhero TV series, “Arrow.”

In the same period, while Katie’s career was rising, David’s own career seemed to be cresting and then slowing down. He publicly acknowledged he had a drinking problem in 2008. And the drinking problem, which he had worked so hard to overcome, was beginning to get the best of him.

The drinking was beginning to affect his work—at first, in small but still significant ways. He began showing up late for sound-checks. He seemed to be chatting a bit more than was ideal (and singing a bit less than was ideal) in some of his concert appearances. He sometimes seemed now, in performances, to be slightly off of his game. Some in the industry felt like he was beginning to slip.

As David began to drink more, he also withdrew more and more into himself. He had less energy to put into his relationships. And he began to age visibly, with the drinking beginning to show in his face.

Alcohol-related charges brought him unwanted publicity. An arrest for driving under the influence (DUI) in Florida in 2010. A DUI arrest in upstate New York in 2013. An arrest for suspicion of DUI in California in 2014. And then in 2015, he was cited in Florida for leaving the scene of a car accident, improper lane change, expired plates and driving on a suspended license. It was all more than he could deal with. He spent days drinking by himself, trying to numb the pain.

Sue Shifrin filed for a divorce in 2014. David filed for bankruptcy in 2015. Everything was slipping away now.

It pained me to see him give a TV interview in which he was clearly under the influence. It pained me to hear of him giving concert performances in which he could no longer remember the words to some of his biggest hits. The alcohol was impairing his memory.

In February of 2017, he fell off of the stage after giving a poor performance in Agoura Hills, California. He announced that he was retiring from performing.

Later that year, he fell in a recording studio and was rushed to a hospital. Doctors determined that he was suffering from liver failure and kidney failure, due to his alcoholism. He was gravely ill. He had told family members and others that he had stopped drinking, but now he was dying. His organs were failing. Longtime alcohol poisoning was taking its toll. “People” magazine quoted him as saying, “I did it to myself, man. I did it to myself to cover up the sadness and the emptiness.”

Family members came to offer support. In David’s final week, he was in and out of consciousness. His daughter Katie, seeing him for the first time in ages, said afterwards that his final words to her were: “So much wasted time.” David passed away on November 21, 2017.

* * *

My visit to David’s hometown, 31 years after I visited it with David, filled me with an unexpected sadness. So many of the stories he had told me were sad ones, from him feeling acutely the absence of his father while growing up; to Hollywood producers working him so hard that he struggled day by day just to cope; to him spending virtually all of his life, once fame hit him, medicated one way or another–whether he was taking prescribed medications to combat depression, anxiety and “nerves,” or “self-medicating” with drugs and alcohol. He had only contempt for anyone he felt had tried to exploit him or use him in any way, large or small, whether they were Hollywood big shots or simply someone he’d once considered a friend.

It was time for me to go now. I didn’t want to leave West Orange, but it was time. I stopped at the gas station (on Harrison Avenue) that was nearest to David’s boyhood home. I put $14 worth of gas in my aging Lincoln, and headed home.

I found myself humming—and then softly singing—a song I’d learned from David. It was a song he told me he liked a lot, even if his recording of it never became a big hit: “The Puppy Song.” And I was remembering the way he used to sing that song, and it made me smile; I could always hear the kindness in him when he sang that song.

Thank You for this further in-depth, Chip, and for for being his friend. Firstly I am so glad he is been honoured in West Orange in his hometown and the place he was truly happy. It’s truly lovely both his children will be there to honor their father and witness this event. I am happy David’s Cassidy Roses are flourishing at the Holy Trinity Church in memory of David.

What a wonderful article. Thank you for sharing this with us and for being such a great friend to David .

Many thanks to Camellia for all her hard work in this wonderful tribute to David, a truly wonderful legacy.💕🌹

I’m so pleased that the family will be there , I wish I could be there.

What a wonderful and insightful article. Thank you for sharing your insights into the very human side of David Cassidy.

To me it’s a tragedy that he lived with so much sadness and pain. While the industry from time to time believed he was a has been, his legions of fans worldwide never did. Everytime the industry gave David a platform, his fans came out in their droves. The tragic person living his compelling and flawed human life was always and is still the super hero of millions, cherished with the deepest love and respect for him as a person, for his immense talents and extraordinary body of work.

A small correction to your story – the USA tends to regard success in that territory as the “be all and end all”. The song you referred to – The Puppy Song – was a massive hit internationally. In the UK, it was a #1 top 40 hit in 1973, as was the album the song came from.

I pray that Iconoclast can do amazing things with David Cassidy’s name and likeness and keep his incredible music alive and celebrated for generations to come.

Chip, Thank you for expanding more on David’s life. I didn’t know of him (except for two episodes of the show … my parents didn’t like it) until the media announced his death. I wish I could have seen him perform.

I began reading and watched everything about David: TV shows, movies, concerts, and his book. The ‘push’ to make David a superstar and all that happened throughout his life saddened me. All the joys of his life outshined by those that took advantage of him … and his personal demons. I know too well how alcohol can become an addictive ‘healing’. In the end, it claims you.

I’m glad there are so many people who did and still love David: that wonderful voice, acting talent, and overall great entertainer! May he continue to shine his light on us.

I read the story and it saddened me thinking what a sad story.

I saw David Cassidy in New York in the 70’s He touched my hand and I had a signed picture of him