Chess

Armed with a new book, this musical drama combining cold war plotting, chess rivalry, and romantic intrigue returns for a Broadway rematch following its 1988 flop.

Aaron Tveit (as Freddie Trumper) and Lea Michele (as Florence Vassy) in a scene from the new version of the musical “Chess” at the Imperial Theatre (Photo credit: Matthew Murphy)

Back in the early 1970s my wife and I bought a bunch of books about chess, learned the game, bought a marble chess set, played for about two years, and never picked up a chess piece again, forgetting everything we knew. I admit to having even less familiarity with Chess, the musical by British lyricist Tim Rice (Jesus Christ Superstar) and Swedish songwriters Benny Andersson and Björn Ulvaeus of the pop band ABBA, who created it.

They saw it become a big hit in London in 1986 but, greatly revised, flop on Broadway two years later. The story of the 1986 original is told in an interesting YouTube documentary called ABBA and the Cold War: A History of Chess the Musical. Another documentary is needed to track its complex, subsequent adventures.

Despite its checkered past, Chess, beginning as a double LP concept album in 1984, has gained legions of fans through its album, hit songs, international revivals, and frequent revisions, some in concert form, some as hybrids mingling other versions. Director Michael Mayer’s vivid, terrifically sung, but hard to love revival at the Imperial Theatre has yet another new book, this one by screenwriter Danny Strong.

Lea Michele (as Florence Vassy) and Nicholas Christopher (as Anatoly Sergievsky) in a scene from the new version of the musical “Chess” at the Imperial Theatre (Photo credit: Matthew Murphy)

The 1988 Broadway book—different from the London original—was by Richard Nelson with Rice’s uncredited assistance. Strong employs most of the characters and essentials introduced in that version, but with fresh dialogue and different gambits in character emphasis and plot development, including the ending (one of the most frequently altered parts).

Chess takes place mainly during the cold war years of the 1980s, when the USA and the Soviet Union were sweating out the threat of nuclear war represented by each side. With international chess matches serving as a metaphor for the political games played by these superpowers, the plot makes use of a CIA agent, Walter de Courcey (Sean Allan Krill), and a KGB agent, Alexander Molokov (Bradley Dean), who is also a mentor and “second” for a leading Soviet competitor. Their duties take them to chess championship matches, like that between an American and a Soviet in Merano, Italy, where the show begins.

The importance to the Soviets of victory in these high-stakes chess matches reveals to what lengths a nation might go in pursuit of favorable propaganda, even when the fate of the world is on the line. While what happens is fictional, we’re informed that some of what we’re watching actually happened.

Bryce Pinkham (as The Arbiter) and the cast of the new version of the musical “Chess” at the Imperial Theatre (Photo credit: Matthew Murphy)

A chief focus, as seen in the show’s ads, is on the romantic triangle formed by 1) American grandmaster Freddie Trumper (Aaron Tveit, Moulin Rouge!), charismatic, psychologically troubled, and self-destructive (inspired by chess enfant terrible Bobby Fischer); 2) Anatoly Sergievsky (Nicholas Christopher, Hamilton), his brilliant, tragically conflicted Soviet rival (inspired by Boris Spassky, Victor Korchnoi, and others); and 3), the beautiful, ambitious Hungarian refugee and chess second, Florence Vassy (Lea Michele, Funny Girl). Her father, incarcerated in Siberia after the 1956 anti-Soviet Hungarian uprising, is a pawn in the CIA-KGB maneuverings.

The shifting professional and emotional relationships among these characters, complicated by the presence of Anatoly’s wife, Svetlana (Hannah Cruz), herself a pawn, provides the fabric against which we view Anatoly’s involvement with Florence. And, of crucial significance to the plot, each member of the central trio is faced with urgent, perhaps life-and-death, choices.

Broadway favorite Bryce Pinkham (A Gentleman’s Guide to Love and Murder) plays an emcee/interlocutor called the Arbiter (i.e., a chess referee), commenting on the action while taking part in it himself. Not only does his cheeky narrative inject what little humor this self-consciously serious show provides, but his remarks are often very meta, including cracks about RFK, Jr., and the name Freddy Trumper. Broadway audiences lap such stuff up, no matter how leaden.

Hannah Cruz (as Svetlana) in a scene from the new version of the musical “Chess” at the Imperial Theatre (Photo credit: Matthew Murphy)

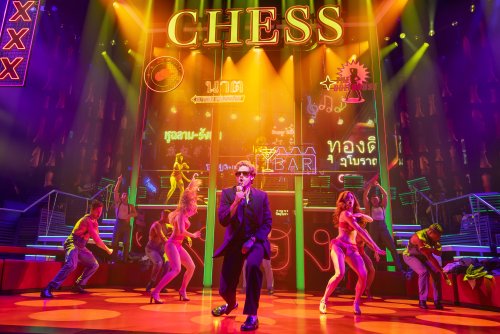

Betrayals, defections, threats, cheating, spying, mental health, psychological manipulation, identity crises, and the like inform the action, not only in Merano and Bangkok, the latter providing the setting for the show’s most popular song, the upbeat “One Night in Bangkok.” It gives the sexy, multitalented singing-dancing chorus one of several opportunities to demonstrate slick moves choreographed by Lorin Latarro, some of which convey a robotic look reminiscent of early Soviet avant-garde theater.

Overall, dialogue is secondary to singing, the music being in a variety of styles, much of it (too much) anthemic and, like Florence’s “Someone Else’s Story,” semi-operatic. My ears still are ringing with the explosive voices of these artists’ nuclear-powered lungs. In one song, “Endgame,” Anatoly holds the word “never” at the top of his voice for what almost seems like minutes; it’s a tour de force but draws attention to the singer, Christopher, more than who or what he’s playing.

Unlike Robin Wagner’s technically complex 1988 set, which used a computerized chessboard-like platform and a series of shifting Greek periaktoi columns that sometimes endangered the actors, David Rockwell’s set—creatively lit by Kevin Adams—is a sleekly elegant composition of two side staircases connected to a central bridgeway, with the orchestra distributed along it. At one point, a rectangular light frame hovering overhead descends to box the characters in. This stripped-down, neutral arrangement, however, evokes the feeling of a concert performance, especially when singers deliver straight to the audience rather than while interacting with others.

Aaron Tveit (as Freddie Trumper) in the Bangkok section of the new version of the musical “Chess” at the Imperial Theatre (Photo credit: Matthew Murphy)

Peter Nigrini’s projections of stills and videos—lots of it cold war-related—play a critical role, but the only permanent visual allusions to the title are rows of large chess pieces incorporated into the design of the frame to the set. Tom Broecker’s beautifully tailored costumes for the mostly well-dressed ensemble add immeasurably to the eye-appeal.

As others have said, Chess’ music is its greatest asset; Rice’s lyrics, often difficult to make out when first heard, aren’t in the same league as those of the great Broadway lyricists, being more narratively functional than verbally clever or otherwise memorable. None of the characters are particularly convincing, each seeming more an efficient outline than someone fully fleshed; they live through the magnetic appeal and eardrum-shattering voices of the show’s stars.

Strong’s book belies his name, its overlong (two hours, 40 minute) narrative, with all its scheming realpolitik, being more formulaic than authentic. Its points about the individual vs. the state, personal ambition vs. national loyalty, truth vs. propaganda, the pressures of celebrity, and so on, are clear, but Chess is too addicted to larger-than-life histrionics to make us more than cerebrally grateful or deeply invested in the choices the characters must face.

Nicholas Christopher (as Anatoly Sergievsky) and the cast of the new version of the musical “Chess” at the Imperial Theatre (Photo credit: Matthew Murphy)

In the end, this Chess may belt to the rafters and flatter the senses, but its stumbling book and cut-out characters keep it from delivering a real checkmate—leaving you admiring the music more than caring who captures the king.

Chess (open run)

Imperial Theatre, 249 W. 45th Street, in Manhattan

For tickets, call 211-239-6200 or visit http://www.Telecharge.com/Chess-tickets

Running time: two hours and 40 minutes including one intermission

Leave a comment