Gingold Theatrical Group’s 20th Anniversary Gala at The Players

The occasion was the 20th Anniversary Gala of Gingold Theatrical Group, the company that celebrates and revitalizes the work of George Bernard Shaw

Richard Weinberg, Julia Weinberg, Donna McKechnie, Danny Burstein, Gray Coleman, Charles Busch and David Staller. Photo by Genevieve Rafter-Keddy

By Jack Quinn, Publisher, TheaterScene.net

December 1, 2025 — The Players, Gramercy Park South

On a clear early-December night, The Players was already buzzing — warm light, familiar faces, and staff moving through with wine. As guests headed upstairs to the Great Hall, it was clear this wouldn’t be a standard gala but a gathering rooted in continuity and shared history.

Charles Busch. Photo by Genevieve Rafter-Keddy

The occasion was the 20th Anniversary Gala of Gingold Theatrical Group, the company that has devoted two decades to celebrating and revitalizing the work of George Bernard Shaw—not as museum artifact, but as living activist theatre. The evening honored three figures whose contributions reflect Shaw’s own principles of rigor, mischief, activism, and humanity: Danny Burstein, Donna McKechnie, and Gray Coleman.

From the moment Artistic Director David Staller stepped forward to open the evening, the tone was unmistakable: warm, candid, politically alert, and defiantly hopeful. “What inspired me as a child,” he began, “was the idea that this is a life we get to create for ourselves — and no one ever has the right to take that away from us.”

David Staller Photo by Genevieve Rafter-Keddy

He then sketched a vivid portrait of Shaw not as the aristocratic wit people assume, but as “a poor, uneducated Irish kid with a speech impediment and bad skin… completely unwanted,” whose mother left early and whose father was “an abusive alcoholic.” Against all odds, Shaw went to London, self-educated at the British Museum, and remade himself through activism, humanitarianism, and art. Staller’s voice warmed as he said, “He helped invent modern English drama, fought for women’s rights, gay rights — at a time when it was illegal — and donated his royalties from Pygmalion and therefore My Fair Lady to build schools, orphanages, and the London School of Economics.”

If Gingold has a thesis, this was it: art as empowerment; theatre as civic action; storytelling as the construction of a more humane world.

Pam Singleton. Photo by Genevieve Rafter-Keddy

The company’s Board Chair, Pamela Singleton, welcomed the audience with the affection of someone greeting family in her living room. “The Players feels like my home away from home,” she said, gesturing up at the walls of theatrical titans. “And I hope as you look around you at the historic figures from the 19th and 20th centuries, you feel as inspired as all of us who love this club.”

Her gratitude to the evening’s honorees was matched only by her praise for Staller. “David has been running this organization for twenty years, which is extraordinary,” she said. “He just completed a very successful run of Pygmalionat Theatre Row, and he continues to steer this company with purpose and courage.”

Courage indeed. When the National Endowment for the Arts informed Gingold that it would “no longer fund arts organizations dedicated to embracing diversity and inclusion,” Staller told the room, “I’m not paraphrasing—that’s exactly what it said.” The loss of promised funding triggered an avalanche: “Some of our longtime funders — closet alt-conservatives — followed suit.” Gingold was forced to cancel two shows for lack of understudies; a community accustomed to generosity suddenly needed its own.

Donna McKechnie, Isaiah Josiah and Danny Burstein. Photo by Genevieve Rafter-Keddy

But on this night, Staller refused despair. “The fact that you’re all here — you got your ass out of bed, you came to be together — that matters. This primal need for community is why theatre exists.” The room erupted in applause. It felt less like a gala and more like a town hall of artists reclaiming their mandate.

The evening’s entertainment was helmed by Thom Sesma and Christine Pedi, two performers whose artistry represents the spectrum of New York theater’s emotional and comedic range.

Sesma — the magnetic actor whose career has encompassed Sweeney Todd, Pacific Overtures, A Man of No Importance, and Assassins, and award-winning performance in this season’s DEAD OUTLAW on Broadway — introduced the musical portion with his trademark elegance: “We’ve put together a serendipitous selection of Shaw,” he said, “and we’re all counting on your sparkling responses, shall we?”

Christine Pedi & Thom Sesma. Photo by Genevieve Rafter-Keddy

Pedi — the beloved “Lady of a Thousand Voices,” known for Forbidden Broadway, SiriusXM, and her incomparable cabaret satire — delivered a torrent of Shaw epigrams with laser-exact timing:

- “Silence is the most perfect expression of scorn.”

- “There is no love sincerer than the love of food.”

- “Life does not cease to be funny when people die, any more than it ceases to be serious when people laugh.”

Her performance was both homage and sparkplug, reaffirming why she’s a perennial favorite at New York galas.

Things then took a delightfully chaotic turn as Pedi performed an imagined Pygmalion scene featuring Eliza Doolittle as played by Elaine Stritch, Bette Davis, Fran Drescher, Liza Minnelli, and Katharine Hepburn. The room howled. “This great play,” Sesma said, grinning, “is truly indestructible.”

The Honoring of Gray Coleman

Gray Coleman, Photo by Genevieve Rafter-Keddy

The first honoree of the night, Gray Coleman, was presented by Staller with affectionate awe. Coleman, a revered entertainment attorney with credits spanning Broadway, Off-Broadway, film, television, institutional theatre, and publishing, has been quietly shaping American theatre for decades. A partner at Davis Wright Tremaine, he has represented a sweeping array of institutions — The Public Theater, Manhattan Theatre Club, MCC Theater, BAM, The Goodman, The Old Globe — and estates ranging from Rodgers & Hammerstein to Agatha Christie.

Staller’s introduction had the comic, runaway energy of a man trying to summarize a life too large for bullet points. “Are you an insomniac?” he teased Coleman. “How does anyone have time for all this?”

Coleman accepted the award with characteristic modesty. He recalled first appearing on a Playbill “staff page” forty years ago — the small-print section listing accountants, lawyers, and marketers. “Those people,” he said, “build the vessel that lets the actors sail.” His speech, elegant in its humility, honored what he called “the invisible architecture” of theater — the people who ensure stories make it to a stage at all.

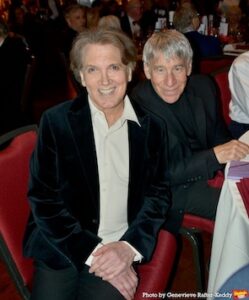

Charles Busch and Stephen Schwartz. Photo by Genevieve Rafter-Keddy

Charles Busch: Wit, Glamour, and Memory

The next performance came from Charles Busch, the playwright-actor-novelist whose career has spanned drag artistry, camp, Broadway success, and cultural iconography. Busch has always been one of The Players’ most beloved figures, and the room warmed instantly as he took the microphone.

He spoke movingly of his long connection to Donna McKechnie and Danny Burstein. “I’ve always felt like the red leaf on the family tree of theater,” he said with his signature dryness. “But whenever I’d see Donna or Danny at an event, they were always so kind. That meant more than they know.”

Busch then sang John Mayer’s melancholy “Please Stay with Me Till After the Holidays,” followed by a luminous, heartfelt rendition of Joni Mitchell’s “Both Sides, Now.” His voice, softened with years of theatrical storytelling, landed with the ache and shimmer of late-December nostalgia.

Danny Burstein. Photo by Genevieve Rafter-Keddy

Honoring Danny Burstein

Staller introduced Danny Burstein with a reverence that filled the room. Burstein — the Tony-winning actor whose performances in Moulin Rouge!, Fiddler on the Roof, South Pacific, My Fair Lady, and Talley’s Folly have made him one of Broadway’s most beloved presences — listened quietly as Staller spoke of his artistry and humanity.

“You get a sense of Danny’s humanity by watching him onstage,” Staller said. He told the audience about a letter his late partner Robert Osborne once wrote to him after seeing Burstein in Talley’s Folly: a moment of shared admiration that has stayed with him for decades.

When Burstein took the podium, he began with humility. “I’m honored to receive this, especially from Gingold, whose mission I love and respect.” His tone shifted as he spoke of Staller personally: “If we’re being honest, what tonight really means is that we all love David Staller.”

He described the bleakest days of the pandemic, when his wife, Rebecca, was suffering from ALS. “There were only a handful of people who showed up every single day to help,” he said. “David was one of those people. I owe him an enormous debt of gratitude.”

It was one of the most emotionally arresting moments of the night — a reminder that art and community are inseparable, and that care is sometimes the purest form of activism.

Stephen Schwartz: A Shavian Resistance Song

Stephen Schwartz. Photo by Genevieve Rafter-Keddy

Then came Stephen Schwartz, the legendary composer-lyricist of Wicked, Pippin, Godspell, Children of Eden, and so many other defining works of the last fifty years. Schwartz, a past Gingold honoree, stepped forward with easy grace.

He spoke with admiration for Gingold’s mission: “I so admire David for keeping the work and spirit of the great George Bernard Shaw alive.” The song he chose — from the forthcoming Wicked Part Two film — was, as he put it, “not quite Shaw in its language, but Shavian in its resistance to dark forces.”

The song, about “loving a place that never loved back,” landed in the room like a parable for the country’s current moment — a reminder that love, whether for a person or a nation, is a choice requiring courage.

Honoring Donna McKechnie

Donna McKechnie, Photo by Genevieve Rafter-Keddy

Staller introduced Donna McKechnie — the Tony-winning original Cassie in A Chorus Line and one of Broadway’s most beloved dancers — with genuine awe. “When I first saw her dance,” he said, “I had never been so emotionally moved.”

McKechnie’s speech was luminous. She described going to Gingold’s Pygmalion this fall, arriving with the “anxiety that accompanies me most days in this upside-down world,” and leaving transformed. “All of a sudden I was in this jewel box of a theater,” she recalled. “The lights dimmed, and I was taken on an exquisite journey. I floated out on a cloud.”

Her gratitude turned fierce as she addressed the audience: “Live theatre brings people together. It saves lives in small ways, in big ways, in necessary ways. And we need it now more than ever.”

Auction, Continuity, and Closing Benedictions

Nick Nicholson, Auctioneer. Photo by Genevieve Rafter-Keddy

After the performances, Nicholas “Nick” Nicholson, the famed auctioneer and raconteur, took the stage to lead a spirited charity auction, joking that “the charming will be separated from the tedious” — and that the audience gets to choose which they’ll be.

The auction lots included rare Al Hirschfeld drawings, a Hirschfeld self-portrait, a hand-written George Bernard Shaw letter with its famously tiny script (“he grew up poor and saved ink,” Staller noted), and a Film Forum membership donated by Gray Coleman, who serves on its board.

The evening closed with a final benediction from Staller — neither sentimental nor naïve, but grounded, Shavian, and deeply felt. “All art is political,” he said quietly. “Everything we do and see and hear. The power of the arts is something we share — to tell our stories, to hear others’ stories. This community, this coming-together, has a power and magic nobody can destroy.”

The applause that followed held the soft, collective exhale of people who had been reminded why theatre matters.

Looking Forward to 2026: Gingold’s Continuity of Mission

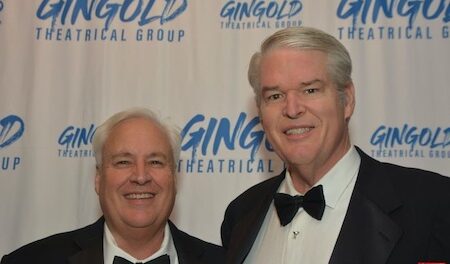

Curtis Strohl and Jack Quinn. Photo by Genevieve Rafter-Keddy

What makes Gingold’s 20th anniversary meaningful is not simply its longevity, but its clarity of purpose. Staller’s interview for TheaterScene’s recent Shaw Symposium cast that purpose in sharp relief.

He founded Gingold in 2005 not as a career move — “I was never unemployed when I wanted to work” — but as an act of civic alarm during the Bush years, when journalists were being fired for speaking out. “I felt I needed to do something not about me, but about us,” he said.

The company grew from six months of experimental readings into two decades of productions, education programs, school partnerships, and activist community building. The work is volunteer-driven, grassroots, and often financially fragile — but sustained by its values.

Looking toward 2026, Staller remains pragmatic and hopeful. Gingold plans to continue:

- Developing new activist plays

- Reinstating staged readings at The Players

- Deepening school and college partnerships

- Hosting ethics and humanities conversations rooted in Shaw

- Producing another full production, if finances allow

Donna McKechnie and Charles Busch. Photo by Genevieve Rafter Keddy

His conviction endures: “Young people are focused, dedicated, determined to fix the world older people like me have messed up.”

If Shaw’s line — “Life isn’t about finding yourself; life is about creating yourself” — is Staller’s private compass, then perhaps the evening at The Players was its public echo: a community creating itself again, insisting upon connection, courage, and the persistent necessity of live theatre.

And as guests descended the broad staircase back into the Gramercy night, the low hum of conversation suggested a roomful of people newly reminded of their place in that ongoing story — grateful, galvanized, and ready to face whatever comes next.

Jack Quinn founded TheaterScene.net in 2001, nine days after surviving the 9/11 tragedy at Ground Zero. Seeking to focus on what’s great about New York rather than what had been lost, he built the site into one of the city’s longest-running theatre publications. Now in its 24th year, TheaterScene.net features the work of ten writers covering productions across the city, while Quinn’s own writing centers on the human stories behind the art — the quiet determination, humor, and heart that keep the New York “theater scene” alive.

photos used with permission from Genevieve Rafter-Keddy

Leave a comment