A Bodega Princess Remembers La Fiesta de los Reyes Magos, 1998

Iraisa Ann Reilly’s one-woman holiday confection is by turns hilarious, tender, and quietly profound, while preserving a cozy “sit down with coquito” embrace.

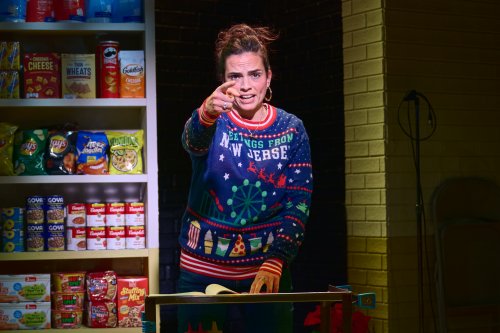

Iraisa Ann Reilly in her one-woman show “A Bodega Princess Remembers La Fiesta de los Reyes Magos, 1998” at Ensemble Studio Theatre (Photo credit: Valerie Terranova)

If you venture into the modest yet industrious confines of Ensemble Studio Theatre for the solo performance, A Bodega Princess Remembers La Fiesta de los Reyes Magos, 1998, you quickly discover that you have not merely purchased a ticket to a show; you have submitted yourself to a full-blown cultural variety hour filtered through the polyphonic memories of its genial host. Within minutes, Spanish-language renditions of “Rudolph, the Red-Nosed Reindeer” and “Frosty the Snowman” waft through the space like nostalgic incense. You may find yourself evaluating (or even participating in) an impromptu talent contest. The evening’s kaleidoscope of offerings extends to a spectral cameo by the late Selena, and a late Celia Cruz, and even a smattering of deftly executed magic tricks, It is, in short, a densely packed ninety minutes, nearly baroque in its layering. And bring your Spanish-English/English-Spanish dictionaries as there are entire conversations without subtitles.

At the beating heart of this merry tumult is Iraisa Ann Reilly’s affectionate, often slyly comic memoir of her 1990s upbringing as a Latina girl in Egg Harbor City, New Jersey—population four thousand, “close enough to Atlantic City to dream big and far enough to remain invisible,” as she might have put it. Director Estefanía Fadul fashions the stage as the titular bodega, presided over by the grandfather and claimed as Reilly’s sovereign childhood domain, becoming the crucible of her imagination. Reilly recalls playing hide-and-seek amid solemn towers of rice bags and swinging Tarzan-like from a twine-and-stick contraption devised by her grandfather in the cleaning-supplies aisle.

She invokes her family’s modest enterprise as nothing less than a humming civic agora, a warmly scuffed nexus where the neighborhood’s daily pageant unfolded with ritual regularity—where every patron was greeted with the ease of long acquaintance and where sustenance could be procured on credit as readily as gossip. (Cigarillos, however, remained firmly outside this benevolent economy, as her grandfather, ever the stern custodian of boundaries, was quick to interject.) No wonder, she wryly observes, that she grew up believing her humble hometown constituted the “center of the world.”

Iraisa Ann Reilly in her one-woman show “A Bodega Princess Remembers La Fiesta de los Reyes Magos, 1998” at Ensemble Studio Theatre (Photo credit: Valerie Terranova)

Reilly’s keen instinct for observational comedy reveals itself early and often. Arrayed in her Sunday-best for a major event at her Catholic parish, she declares, “I looked like an American Girl doll. One of the ethnic ones.” When describing the delirious televisual stew that was the Spanish-language juggernaut Sábado Gigante, she offers a formulation so precise it deserves preservation in amber: “If you took Johnny Carson, American Idol, The Price Is Right, and Sixty Minutes, and put them in a blender in a studio in Miami, you would have something sort of close to Don Francisco’s Sábado Gigante,” that gloriously overstuffed, endlessly rollicking variety hour that once functioned as a de facto weekly family convocation for Univision’s vast and varied viewership.

She is never more incandescent than when summoning the memory of a homespun, live-on-stage facsimile of Sábado Gigante as she ushers us into the basement cafeteria of St. Nicholas School in Egg Harbor City. Reilly resurrects the program’s talent competition in all its gaudy splendor: El Chacal’s trumpet blares with comic brutality, dispatching the unlucky as we, now a temporary congregation of devoted nostalgists, bellow in unison,” Y fuera! And reflecting on her family’s bifurcated holiday traditions—a mingling of Cuban and American customs—she notes that while Santa delivered on December 25, the Three Kings assumed responsibility for follow-up logistics. Batteries for toys, for instance, were strictly an Epiphany affair. For a child craving instant gratification, this was “exquisite torture.”

Reilly’s performance is nothing short of a shape-shifting marvel, a one-woman fugue of voices and visages. She does far more than sketch the outlines of a memory; she immerses us in it, salting the narrative with those precisely observed, idiosyncratic details that grant the past the immediacy of breath. At one point, chuckling at the absurd grace inherent in cultural ritual, she observes, “If you’ve never tried to dance merengue in a cafeteria built for second graders, I promise you, it’s a spiritual experience.” With only the slightest recalibration of her spine or a flickering alteration in the light of her eye, she summons an entire chorus of kin and community: a cacophony of aunts, uncles, neighbors, and stray personalities who populate her remembered world with the unruly tenderness that is the lifeblood of familial lore. Each figure arrives startlingly complete, as though conjured from the ether fully breathing, fully feeling. And crucially, Reilly deploys these incarnations not merely as fodder for laughter—though the comedy lands with precision—but as vessels for clarity and revelation, their humor braided with the deeper resonances of lived experience.

Iraisa Ann Reilly in her one-woman show “A Bodega Princess Remembers La Fiesta de los Reyes Magos, 1998” at Ensemble Studio Theatre (Photo credit: Valerie Terranova)

Reilly, with a performer’s instinct for reclamation, structures her show around the liturgical anchor of January 6—the Feast of the Epiphany, that moment when the Magi kneel before the Christ child—using the church’s annual celebration as a loose scaffolding upon which she drapes her recollections. She wrests the day back from its recent Trump era defilement by recounting her own far more wholesome insurrection: a community talent show in which she bravely attempted “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” en español, only to find the lyrics dissolving from memory at the crucial moment. What emerges is a miniature parable of perseverance, framed by her immigrant parents’ recollections of the formidable gauntlet they ran to ensure that their daughter might someday stand—spotlit, quivering—upon that stage.

The memories arrive in jovial abundance: warm, witty, and imbued with an understated melancholy born of familial sacrifice and the perpetual negotiation of identity in a predominantly white enclave. She is a charming raconteur, offering the audience a half-smile tinged with mischief. “How many of you remember the Macarena?” she inquires, sweeping the room with a knowing gaze. Upon receiving hesitant responses, she pronounces, “Some of you do, and the rest of you are liars.” Her ease in drawing spectators onstage is formidable—“Yes, this is interactive,” she warns, with mock menace—and on any night volunteers materialize with alacrity. She recalls, with gimlet-eyed accuracy, the perilous politics of church dance competitions: “Two ways to get voted out. One: too much use of the hips. The other: not enough use of the hips. You had to find the right balance, staying true to your ancestors and not being a ho.”

Yet alongside these comic vignettes lie the shadows that shaped her family’s narrative: her grandparents’ harrowing departure from Cuba. As she revisits the memory of overhearing a family conversation about what her relatives carried with them upon their first, trembling arrival in the United States, the buoyant rhythm of the evening slackens —so beautifully, deliberately. She halts, gazing out at us with a mixture of timidity and steel, and poses a question so disarmingly simple it becomes nearly metaphysical: “If you had to leave everything behind… what would you fit into one bag?” The words hang there, weightless and devastating. A hush falls—one of those rare, oxygen-thin theatrical silences in which even the electric hum of the lighting grid asserts itself. In a performance saturated with laughter and warmth, the moment lands with the tremor of a minor earthquake, quietly rearranging the emotional architecture of the room. There is also the childhood sting of linguistic misalignment—being shunted into a special-education trailer not because of deficiency, but because her Spanish (honed by fervent telenovela consumption) outpaced her English.

The production’s design components support this scrapbook sensibility with admirable restraint. Fadul has assembled a great team to flesh out this vision. Rodrigo Escalante’s set—evocative of a church-basement cabaret—suggests both sacred fellowship and after-hours conviviality. Carolina Ortiz Herrera’s lighting washes the space in vibrant hues, as if blessing each memory with its own chromatic signature. Milton M. Cordero’s projection design provides a lively visual counterpoint: clips from Sábado Gigante, a spirited promo for NBC’s The World’s Greatest Magic (in which the performer once moonlighted as her brother’s glamorous assistant), and, most deliciously, archival footage from the 1996 Democratic National Convention featuring Hillary Clinton—and yes, a rhythmically challenged Al Gore—performing the Macarena. The sound design team—Daniela Hart, Bailey Trierweiler, Noel Nichols, and Uptown Works—supplies an eclectic soundscape of ticking metronomes, trumpets, ambient murmurings, and a playlist fit for communal lip-synch.

Viewed through the luminous, gently ironic gaze of its young protagonist, the piece becomes a vivid palimpsest of an American community in the throes of transition. What might have lapsed into cliché is instead suffused with the cozy inevitability of a beloved Christmas film—the sort one revisits annually not for surprise, but for the warming reassurance of its ritual pleasures. Reilly, with her beguiling fusion of arid wit and enveloping stage warmth, ensures that the experience feels less like repetition than familiar tradition.

Reilly, though a gifted mimic—her gallery of housewives, curmudgeonly elders, and a radio-DJ-turned-priest who sermonizes as if announcing a “groovy new platter” is especially choice—sometimes falters when grounding the evening in her unadorned self. Her pacing, at moments, skews hurried, robbing certain passages of the luxuriant savor they deserve. Fadul might judiciously trim and reorder the material, encouraging Reilly to lean into her natural warmth as the evening’s emcee. Still, the raw ingredients shimmer with promise. A Bodega Princess Remembers…, co-produced by Ensemble Studio Theatre, the Lucille Lortel Theatre, and the Latinx Playwrights Circle, could—with deft pruning—mature into a piece with the legs to stride confidently across black-box stages nationwide. One can easily imagine it as a cherished annual offering, a festive-season balm for audiences seeking merriment seasoned with poignancy. Before such a future can be realized, however, the show requires a bit of judicious unstuffing—less overpacked Nochebuena stocking, more carefully curated reliquary.

A Bodega Princess Remembers La Fiesta de los Reyes Magos, 1998 (through December 14, 2025)

Ensemble Studio Theatre, Lucille Lortel Theatre and Latinx Playwrights Circle

Ensemble Studio Theatre, 545 West 52nd Street, in Manhattan

For tickets, visit www.ensemblestudiotheatre.org

Running time: 90 minutes without an intermission

Leave a comment