Nothing Can Take You from the Hand of God

Tullock, Winters & Mezzocchi unravel faith, memory & myth with dazzling complexity—offering not one truth, but a fractured, haunting multitude.

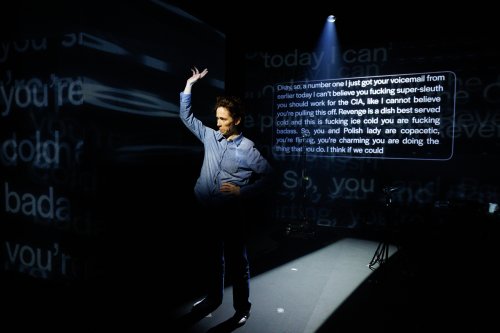

Jen Tullock in the one-woman play “Nothing Can Take You from the Hand of God” at Playwrights Horizons (Photo credit: Maria Baranova)

In Nothing Can Take You from the Hand of God, the mesmerizing new one-person play crafted by Jen Tullock and Frank Winters under the multimedia sorcery of director Jared Mezzocchi, memory itself becomes the stage—a mutable, treacherous terrain upon which fact, fiction, faith, and selfhood vie for dominance. At the heart of this layered theatrical kaleidoscope lies a memoir within the play—Never the Twain Shall Meet: Losing God and Finding Myself, a literary Molotov cocktail tossed squarely at the heart of an evangelical stronghold: the Northeast Christian Church of Louisville, Kentucky. If the name rings with the unmistakable resonance of real life, it should. The church is not only fictional but a mirror held up to an actual congregation in the very city where Tullock herself was raised, cradled and constrained by a similarly evangelical institution.

In this autofictional landscape—where fact and fabrication perform a tango too close to call—Frances Reinhardt, the ostensible author of the incendiary memoir, emerges first as a queer folk hero, the truth-telling survivor of a childhood shaped by spiritual violence and exorcism. Yet the longer one sits in the dim glow of this complex theatrical meditation, the more that moniker begins to fray. Yes, the church is a villain in her narrative, perhaps even a deserving one—but the play, to its great credit, refuses to leave us with the comforting binaries of oppressor and oppressed.

Instead, Nothing Can Take You from the Hand of God invites us to peer into a fragmented mirror, shattered not by malice but by the sheer volatility of recollection. Memory, in this telling, is no static archive but a living organism—bruised, shifting, contradictory. Tullock, who performs every character in the piece with chameleonic dexterity, evokes not just individuals but entire ecosystems of belief, betrayal, and belonging. The result is not so much a solo performance as a tightly orchestrated psychological fugue.

Emmie Finckel’s set design, in its stark simplicity, evokes the unadorned austerity of a literary talkback hastily arranged in the fluorescent purgatory of a suburban Barnes & Noble. Center stage sits a nondescript table flanked by two utilitarian folding chairs—objects so resolutely ordinary they practically hum with banality. And yet, in their very neutrality, they become a kind of blank canvas upon which the complexities of identity, performance, and recollection are projected. The setup is deceptively plain—an anti-spectacle—that cunningly mirrors the play’s investigation of constructed narratives and the illusion of authority in storytelling spaces. Finckel’s choice resists theatrical flourish, insisting instead on the unembellished immediacy of a public event and the quietly charged atmosphere of confrontation disguised as conversation.

Jen Tullock in the one-woman play “Nothing Can Take You from the Hand of God” at Playwrights Horizons (Photo credit: Maria Baranova)

The story spirals outward from the memoir’s publication—a celebratory launch event featuring an all-too-recognizable literary moderator (smug, earnest, over-rehearsed), whose glowing introduction to Frances’ work is immediately juxtaposed with a bone-chilling voicemail from Frances’ agent: the church has gotten an advance copy. Legal action looms. Unless, of course, Frances can get the people she wrote about to confirm her version of events. “Truth,” after all, remains the best defense against defamation.

And so begins a homecoming—less triumphant than tactically necessary—as Frances returns to Louisville in search of affidavits and absolution. What she finds is less like corroboration and more like confrontation. The past, it turns out, is not a stable edifice, but a house of mirrors, with every reflection offering its own accusation.

There’s her brother Eli, who has stayed within the folds of evangelical Christianity, even as he’s spun off his own worship circle. Their mother, RaeLynn, who remains devout and active in the same church that, according to Frances’ book, once subjected her to brutal physical punishment. There’s also a former classmate, now openly gay and married to a man, who has chosen not exile but integration—still part of the community Frances fled. And most pointedly, there is Agnieszka, the Polish missionary whose shared mission trip with Frances once blossomed into love, or something close to it, and who now lives in the church’s mission house, raising a soon-to-be-gay son and navigating her own uneasy allegiances.

Each of these characters appears not only in the narrative but in the flesh—or rather, in Tullock’s gorgeously rendered embodiment of them. Aided by glitchy light cues and pinpoint shifts in vocal register, she sketches a dozen individuals with specificity and restraint. Her Agnieszka is particularly haunting: restrained, precise, a woman whose guarded reserve barely conceals a reservoir of private conflict. Tullock’s accent work, unassisted by a dialect coach, is admirable not for its mimicry but for how it becomes a tool of dramaturgical clarity—helping the audience locate not just geography, but identity.

Jen Tullock in the one-woman play “Nothing Can Take You from the Hand of God” at Playwrights Horizons (Photo credit: Maria Baranova)

If the play’s dramaturgy rests on a latticework of timelines and perspectives, its aesthetic is equally polyphonic. Mezzocchi’s bravura use of live video, here executed by projection designer Stefania Bulbarella, slices the stage into competing visual layers. Characters appear in duplicate, refracted across screens. Loops and lags mimic memory’s halting rhythms. At times, these multimedia elements dazzle—particularly in moments like Frances’ appearance on a fictional CNN segment, or in the cacophony of audience questions at the book reading, masterfully rendered by Evdoxia Ragkou’s sound design. Yet there are also moments when the technological layering purposely becomes a veil rather than a lens—obscuring rather than illuminating.

Encircling Tullock like silent sentinels, three cameras mounted on tripods become integral performers in their own right—capturing, reframing, and ultimately distorting the live action through the alchemical lens of Bulbarella’s kaleidoscopic projection design. These live feeds do not merely document; they dissect and multiply, splintering Tullock’s performance across surfaces and timelines in a dizzying cascade of image and echo. The result is a force-multiplying visual grammar that lends the production a distinctly cinematic texture—at once intimate and expansive, tactile and ghostly. Under the moody, chiaroscuro-leaning lighting of Amith Chandrashaker—whose palette occasionally threatens to tip into obfuscation—the play becomes a flickering palimpsest of selves and stories. It’s a visual landscape where memory doesn’t simply resurface but refracts, and where seeing something from every angle doesn’t necessarily bring it into clearer focus.

Such excess feels thematically justified. The play is not aiming for coherence; it is staging the impossibility of coherence. Frances herself is never allowed to fully cohere. We hear her first not onstage, but in voicemails—her cool, neutral West Coast voice standing in marked contrast to the Kentucky inflections of Eli and RaeLynn, or the crisp Polish of Agnieszka, or the broguish tones of Kenny Weaver, an Irish missionary. She is both narrator and unreliable witness. She is simultaneously seeking truth and curating her image. And the more we see her—especially in the casual cruelty with which she manipulates Agnieszka—the more the seams begin to show. Is she a survivor, telling her story at last? Or is she an author intoxicated by narrative power, rearranging the past for maximum emotional payoff?

Winters and Tullock refuse to answer these questions. Instead, they let them echo. “…people are capable of both true horror and profound kindness, and that we over-simplify our oppressors at our own peril,” they write in a program note—a line that reverberates through every motherly embrace that belies abuse, every church official who acts as both caricature and human being, every sibling interaction where old hurts and enduring love collide. The family, after all, is the first theater we are cast into. And sometimes, its scripts are the hardest to rewrite.

Jen Tullock in the one-woman play “Nothing Can Take You from the Hand of God” at Playwrights Horizons (Photo credit: Maria Baranova)

Audience members at Frances’ book launch pose their own questions—some adoring, others incisive. One asks whether writing the memoir has changed her memory of events. Another suggests that the book’s narrative arc might be at odds with what really happened. The play leaves those questions hanging, their lack of resolution becoming its emotional climax.

For all its intellectual rigor and metatheatrical pyrotechnics, Nothing Can Take You from the Hand of God is most remarkable for its emotional honesty. It understands that people are capable of both horror and grace, that belief can wound and heal in the same breath, that no one person owns a story. In an age when so many narratives are flattened for virality, here is a play that insists on messiness, on multiplicity, on the irreducible complexity of being alive. It is not, thank God, a neat play. But it is a necessary one.

Nothing Can Take You from the Hand of God (extended through November 16, 2025)

Playwrights Horizons

The Peter Jay Sharp Theater, 416 West 42nd Street, in Manhattan

For tickets, visit http://www.my.playwrightshorizons.org

Running time: 70 minutes without an intermission

Leave a comment