The American Soldier – An Interview with Douglas Taurel

In The American Soldier, Douglas Taurel gives voice to generations of service through real letters, lived experience, and fourteen sharply drawn characters. In this conversation, he speaks about honor, sacrifice, brotherhood, and the careful craft required to carry other people’s grief onstage—night after night—without ever letting it become abstract.

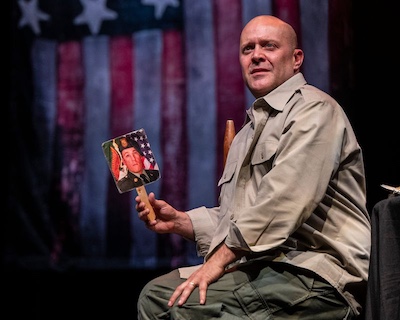

Douglas Taurel in THE AMERICAN SOLDIER. photo by Teresa Castracane Photography

Interview by Jack Quinn, Publisher

Jack

When someone watches The American Soldier, what is the one emotional truth you hope sits with them on the train ride home?

Douglas

Honor. Service. Sacrifice.

The play gives voice to the men and women who raised their right hand and chose to defend us. What I try to do is peel back the curtain on the phrase “Thank you for your service.” We say it so easily, but it often becomes a throwaway line.

Service means a father deployed multiple times. It means a child growing up without their parent at the kitchen table. It means a mother saying goodbye to her son at the Vietnam Memorial Wall. When we say “thank you for your service,” I want us to understand what that actually costs.

Jack

You perform fourteen characters. Which one arrived first? And which one surprised you by refusing to leave?

Douglas

The first piece came from the Revolutionary War—drawn from the diaries of Joseph Plumb Martin and Ebenezer Fox. I came out of the World Trade Center on 9/11, and later, as we were deep in the Middle East, I felt compelled to remind people what this country was founded on and what service has always meant.

The piece that refuses to leave is the Civil War letter from Sullivan Ballou—“Dear Sarah.” He writes that if it’s necessary for him to fall on the battlefield for his country, he is ready. That line runs through the entire play.

As much as these men and women want to be home, they feel compelled to serve. That’s been true from the Revolution to World War I, World War II, Vietnam, and after 9/11, when thousands volunteered. That sense of duty doesn’t disappear with time.

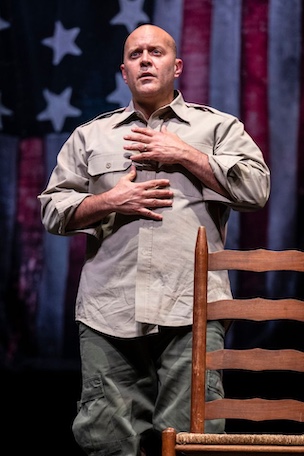

Douglas Taurel in THE AMERICAN SOLDIER. photo by Teresa Castracane Photography

Jack

You’re telling stories that belong to other people—stories of pain. How do you hold that responsibility?

Douglas

Very carefully. Very respectfully.

I stay close to the families. Many have seen the play multiple times. That’s why I’ve never published it. I don’t want anyone handling these letters without care or permission.

At some point, the play will outgrow me. But for now, I hold it close—because these are real people, real losses, real voices that deserve protection.

Jack

Was there a moment in your research that felt too heavy to bring onstage?

Douglas

Jeffrey Luce.

There’s a father-son throughline in the play, and the moment when a father holds his Marine son as a baby and tells us it’s the last time he ever will—that’s brutal. Early on, it was overwhelming. I had to learn restraint.

You don’t do the work for the audience. Let them do it. Sometimes if the actor cries too much, the audience can’t.

Jack

How does performing in civic institutions like the Kennedy Center differ from performing off-Broadway in New York?

Douglas

New York audiences are deeply trained. You feel the critique. The bar is high—and that’s what makes the work better.

Douglas Taurel in THE AMERICAN SOLDIER. photo by Teresa Castracane Photography

In D.C., veterans often set the tone. They lead the room. It’s not more forgiving—it’s different. New York’s rigor sharpens the work. That pressure elevates art.

Jack

What have veterans told you after performances that’s stayed with you?

Douglas

They’ve given me far more than I could ever give them.

Medals, letters, patches—but more importantly, friendship. Many tell me, “You may not have served, but you’re serving now.”

What I’ve learned is this: they’ve been to the darkest places imaginable, and many still find a way back to the light. That matters. That lesson applies to all of us.

Jack

As an actor, you move from grief to humor in minutes. What transition is the steepest climb?

Douglas

From trauma to humor.

But it’s necessary. You can’t leave an audience marinating in pain. Let them touch it—then pull them forward. Theater isn’t about wallowing. It’s about movement.

Jack

Is there a chapter of this story you haven’t fully explored yet but feel pulling at you?

Douglas

The withdrawal from Afghanistan.

Not politically—historically. It mirrors Vietnam. Many veterans are asking, “What was it for?” I’ve added a small piece, The Soldier in the Shadow. There’s more there, and I want to handle it carefully.

Jack

Is there a question you wish people asked you about the work—but rarely do?

Douglas

You asked it: How do you warm up?

People think memorization is the hard part. I wish it were. The real work is preparing the body and instrument. That’s the craft—and it’s invisible unless someone asks.

NewYorkRep presents The American Soldier, a celebrated solo play written, conceived and performed by Douglas Taurel. The limited three-week engagement runs December 2 -21 at A.R.T./ New York (502 W. 53rd Street). Opening night is Thursday, December 4 at7:30PM. Tickets are now on sale atTicketTailor.com.

Author’s Note:

Jack Quinn founded TheaterScene.net in 2001, nine days after surviving the 9/11 tragedy at Ground Zero. Seeking to focus on what’s great about New York rather than what had been lost, he built the site into one of the city’s longest-running theatre publications. Now in its 24th year, TheaterScene.net features the work of ten writers covering productions across the city, while Quinn’s own writing centers on the human stories behind the art — the quiet determination, humor, and heart that keep New York theatre alive.

Leave a comment