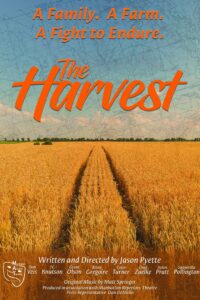

The Harvest

In a Montana farmhouse worn thin by grief and memory, "The Harvest" exposes the fractures beneath a family’s final crop. What begins as a quiet drama of duty erupts into a raw reckoning—where a mother’s long-silenced truth rewrites everything her children thought they knew.

James Carthage, Jr. (TC Knutson) and Sarah Pinnelly (Tylyn Turner) in “The Harvest” at the Chain Theatre ( Photo credit: MariAnn Ryan Skoyen Photography)

Review by Jack Quinn, Publisher

Under the dimming light of a Montana living room, The Harvest plants its story in soil that feels both literal and deeply emotional. The set — all worn linoleum, a sagging doorframe, and a wall crowded with family photographs — has the lived-in authenticity of a place where years accumulate like dust. The moment the lights go down, the room breathes with a faint aura of mustiness and memory. It does not smell, of course, but it feels like it might: a home saturated with weather, grief, and the grind of daily survival.

Director Jason Pyette, who also wrote the piece, shapes the entire first act with patient precision. The sounds of wind, distant machinery, and a radio forecast drift in as if reporting on the family’s emotional state — change coming, slowly, if at all. Here, the pacing feels exactly right. Nothing drags. Nothing rushes. It moves with the rhythm of a place where silence is as expressive as speech.

The story unfolds as the Carthege family navigates the final harvest after the death of their patriarch. But from the outset, what’s truly at stake is intangible. Early on, in a line that lands like a plea disguised as duty, Sarah says:

The story unfolds as the Carthege family navigates the final harvest after the death of their patriarch. But from the outset, what’s truly at stake is intangible. Early on, in a line that lands like a plea disguised as duty, Sarah says:

“Harvest needs to happen. Dad can’t do it. John can’t do it all alone. And this family needs something to pull it together.”

It becomes the play’s quiet thesis: the crop in the field is not the harvest that matters most.

The living room — in Casey James’ detailed technical direction — becomes the emotional center of the home. It’s where the family’s memories seem to hover most densely, especially along the wall of pictures. Those framed moments shape the audience’s understanding before a single argument erupts: this is a family whose story was written long before today’s crisis.

The ensemble works with a grounded naturalism that avoids sentimentality for its own sake. Tylyn Turner as Sarah Pinnelly brings steadiness and an understated moral clarity that anchors the play. Chad Zuelke, as John Carthege, gives us the son who stayed — weary, competent, burdened. His physicality alone tells the story of someone who has worked the land long enough to carry it in his bones.

The sibling dynamic feels most layered between John and Dr. Grant Olson’s Alan, the brother who left home early and built a life elsewhere. Olson’s performance is edged with impatience and defensiveness — the familiar armor of the sibling who claims distance but can never fully escape the family gravity.

And then there is the mother.

As Anna Carthege, Pam Veis gives the most quietly commanding performance in the production. At the beginning, she barely speaks — folding laundry, clearing surfaces, smoothing tension before anyone admits it’s there. Yet she communicates volumes through posture, restraint, and a gaze that sees more than she ever verbalizes.

When she finally speaks fully — confronting her children’s revisionist memories of the farm — the entire play pivots. Veis delivers the monologue with such emotional clarity that the audience seems to inhale as one. Her insistence that the farm was not an anchor dragging them down but the life she built, year by year, alongside her husband of forty years, reframes the story:

Aylan Pratt as Samuel Carthege in “The Harvest” at the Chain Theatre (Photo credit: MariAnn Ryan Skoyen Photography)

This is not a play about escape. It’s about inheritance — emotional as much as agricultural.

The sharpest moment of the night occurs not with Anna’s monologue, but when Sarah confronts Alan about their younger brother Samuel (played with open vulnerability by Aylan Pratt). The script’s language is plain and devastating, and Turner handles it with surgical precision.

She recalls the family photo that scarred Samuel’s childhood:

SARAH: “When Samuel came in from his room, he was happy. He bought a new shirt just for the picture. Somehow, he’d gotten to town to buy a shirt with his own money. He was only a kid, but he thought this picture was so important that he went out and bought his own shirt. But it wasn’t a farm shirt. It was different. A little flashy, maybe, but mostly just different. You made fun of him. You ridiculed him.”

(Pause.)

“You said he looked like a ‘homo.’”

Turner’s delivery freezes the room. Olson’s face tightens — not in villainy, but in recognition. It’s the moment the family’s years of suppressed hurt come to a boil, and the audience can feel the oxygen leave the space. What began as a play about a failing farm becomes a story about the words that lodge themselves in a person’s memory and never quite leave.

Brian Gregoire as Micky Carthege, Tylyn Turner as Sarah Pinnelly, Dr. Grant Olson as Alan Carthege and TC Knutson as James Carathege, Jr. in “The Harvest” at the Chain Theatre (Photo credit: MariAnn Ryan Skoyen Photography)

Brian Easton’s lighting design charts the day’s progression but also something more internal: the slow shift from brittle morning clarity to twilight reckoning. The storm sequence — paired with Andi Daniel’s sound design — gives the sense of a world cracking open just enough to let truth spill out. Angela Riggin’s costumes further the realism: denim exhausted by labor, shirts sun-bleached into resignation, clothes that speak long before the characters do.

By the final moments, when Anna commands her family — and perhaps herself — to move forward by returning to the harvest (“Start by getting the damn crop cut”), the light softens into a gold that looks like forgiveness. Not resolution. Not absolution. But possibility.

The Harvest doesn’t end triumphantly. It ends honestly. And in this production, honesty feels like a kind of grace. The family is not fixed. They are not whole. But after this long day, they are no longer stuck in the same story.

In a landscape of theater that often relies on spectacle or irony, Montana Actors Theatre delivers something rarer: a drama that trusts its silences, its actors, and its audience to find meaning in what is not said aloud.

And as I walked out of the theater, I felt something I didn’t expect at the beginning — something that arrived slowly, the way truth does: a glimmer of hope for the Carthege family, and maybe for any family brave enough to confront the stories they’ve long avoided.

The Harvest (through November 22, 2025)

Montana Actors’ Theatre

Chain Theatre

312 West 36th Street, Floor 4, in Manhattan

For tickets, visit Montana Actors Theatre

Running time: one hour and 45 minutes including a ten minute intermission

Leave a comment