ON THE TOWN WITH CHIP DEFFAA: ON “FUNNY GIRL,” ETHNIC CASTING, AND FANNY BRICE…

Brice—as a pioneering Jewish female Broadway star who took charge of her own fabulous career in an era when few women did—became a source of inspiration for many aspiring young Jewish performers. At her peak, Brice was the highest-paid American singing comedienne.

[avatar user=”Chip DeFFaa” size=”96″ align=”left”] Chip DeFFaa, Editor-at-Large[/avatar]There’s been a good deal of chatter of late—on chat boards, blogs, Facebook pages, and more—over whether the role of Fanny Brice, who was Jewish, should only be played by an actor who is Jewish. Lately I’ve seen some people raise objections to Lea Michele playing Fanny in “Funny Girl” on Broadway because Michele—whose father is Jewish and whose mother is Roman Catholic—does not identify as Jewish. (She was raised Roman Catholic.)

And others have objected to the recent casting of KaterinaMcCrimmon—a Cuban-American from Miami–to play Brice in the national tour of “Funny Girl,” again arguing that Brice should be played only by an actress who identifies as Jewish. Getting this highly coveted role is a big break for McCrimmon. She appeared briefly on Broadway in the short-lived 2019 revival of Tennessee Williams’ “The Rose Tattoo” but is still essentially an “unknown.” However, her getting the role of Fanny Brice made headlines as far away as Israel. The Times of Israel printed: “US tour of ‘Funny Girl’ casts non-Jewish actor as Fanny Brice, reigniting criticism.”

Samantha Massell, who played Hodel (one of Tevye’s daughters) in the 2015 Broadway revival of “Fiddler on the Roof,” expressed on Instagram her anger that the role of Fanny Brice was going to someone who was not Jewish. She posted: “I have no doubt that Katerina is freaking terrific and … that she is more than capable of leading a nat’l tour. But if you consider yourself an advocate for representation in casting and you’re A-OK with this (or celebrating it), you need to check yourself.”

Jennifer Apple—an actor who unsuccessfully auditioned for the role of Fanny Brice and believes the role should only go to someone Jewish—was quoted in The Times of Israel as saying of Brice: “She was a Jewish icon. She was a heroine. She in–and–of–herself paved the way for performers like myself to be able to have a career. If it wasn’t for her, and her chutzpah, many of us Jewish women specifically wouldn’t be able to be performers. So it’s integral to this role, specifically.”

Brice—as a pioneering Jewish female Broadway star who took charge of her own fabulous career in an era when few women did—became a source of inspiration for many aspiring young Jewish performers. At her peak, Brice was the highest-paid American singing comedienne.

Beanie Feldstein said in interviews that playing Fanny Brice was a lifelong dream of hers. (Her birthday party, when she was just three years old, had a “Funny Girl” theme, she’s recalled.) She told the New York Jewish Week last year: “I truly believe that any Jewish woman who wants to be funny and perform and sing owes something to Fanny Brice.” I get that. Totally.

But I’m not persuaded by the arguments that only a woman who’s Jewish could—or should—play Brice.

Actress Fanny Brice (Photo by John Springer Collection/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images)

As someone who’s studied Brice for much of his life—and has written and directed several different shows about her, and has produced albums of Brice’s rare (and in some cases, never-before-released) recordings drawn from my personal collection–I’d like to discuss this issue a bit. Should the role of Fanny Brice only go to actors who identify as Jewish?

I’d like to share a point of view that no one, to my knowledge, has yet brought up in this ongoing debate: Fanny Brice’s point of view. Because the ethnic or religious background of performers who might play Fanny Brice was not an issue for Brice herself. Or for her family.

Brice (1891-1951) was a legendary entertainer. There was talk in Hollywood, while Brice was still alive, about making a film about her life. Asked who would be the bestactor to portray her, Brice answered without hesitation: “There’s one dame who could play me—Joan Davis.” Davis, the actor whom Brice herself wanted to portray Brice back in the 1940s, happened to be Roman Catholic. But—more important–Joan Davis was also funny, she had guts, and she could sing. Brice saw a lot of herself in Davis.

Davis died in 1961 at the age of 48, after several years of declining health. She was interred in a mausoleum at a Roman Catholic cemetary, Holy Cross Cemetary in Culver City, California. She never got a chance to play Brice, whom she’d known and liked.

But it is significant that Brice herself did not feel it essential that she be portrayed by someone Jewish. Neither did Brice’s family. Fanny’s son-in-law, Ray Stark, was the driving force behind “Funny Girl.” He devoted many years to making a reality the show that eventually became known as “Funny Girl.” He wanted Fanny Brice’s legacy preserved. He produced the Broadway musical “Funny Girl” (which opened in 1964) and the subsequent film adaptation (1968) and its sequel, “Funny Lady” (1975). Stark and his wife, Frances Brice Stark (the daughter of Fanny Brice and Nick Arnstein), gave a lot of thought to who could play Fanny, who could play Nick (Fanny’s famed gambler/con man husband, who was born in Berlin to a Jewish father and a Christian mother, and was raised Episcopalian), and who could play Fanny’s formidable mother, Rose, who was born in Hungary to Orthodox Jewish parents.

Before Barbra Streisand was ultimately chosen to star in “Funny Girl,” various performers—both Jewish and non-Jewish—were considered by the family to be acceptable possible Fanny Brices, including Anne Bancroft, Mary Martin, Carol Burnett, Eydie Gorme….

Fanny’s daughter, Frances, wanted Anne Bancroft to portray her mother. Bancroft— whose real name was Anna Maria Luisa Italiano—was the daughter of Italian immigrants, and she was raised Catholic.

whose real name was Anna Maria Luisa Italiano—was the daughter of Italian immigrants, and she was raised Catholic.

Bancroft was a superb actor, who always performed with conviction. But in the end “Funny Girl” composer JuleStyne successfully argued that only Barbra Streisand—who had far greater vocal chops than the other performers under consideration—could fully do justice to the challenging score that Styne and lyricist Bob Merrill were creating.

The Irish-American Kay Medford (whose real name wasMargaret Kathleen Regan) was chosen to play Fanny’smother, Rose, in the original Broadway production—and she played the role of that strong, proud Jewish mother to perfection. (Kay Meford was a wonderful scene-stealer and I doubt if any audience members ever imagined that she wasn’t Jewish.)

Sydney Chaplin (born in Beverly Hills), who originated the role of Nick Arnstein (born in Berlin), was not Jewish or part-Jewish. Neither was the actor who succeeded Chaplin in the original Broadway production, Detroit-born Johnny Desmond (real name: Giovanni Alfredo De Simone), whom I saw in the production back then and enjoyed a lot.

Nor were actors Omar Sharif (who was born in Egypt and converted from Christianity to Islam), who so memorably portrayed Arnstein in the film of “Funny Girl,” or RaminKarimloo (who was born in Iran), who’s played Arstein in the current Broadway revival. But all created generally well-received portrayals of Arnstein.

Incidentally, the real Nick Arnstein was still alive when “Funny Girl” opened on Broadway—sharing an apartment with Fanny’s brother, Lew Brice. Although Nick and Fanny had divorced decades earlier, Nick was still considered part of the family. Producer Ray Stark and his wife, Frances Brice Stark (the daughter of Fanny and Nick), helped give Nick financial support. And they wanted him to be happy with “Funny Girl.” Or at least to be not unhappy with how he was portrayed. He certainly voiced no complaints about the handsome, dashing, urbane actors chosen to play him—who were better-looking, many felt, than Arnstein actually was. (Although Arnstein was always gorgeous in Fanny Brice’s eyes.) But did it really matter if the actors portraying Brice, Brice’s mother, or Nick Arnstein were exactly like the people they were playing? Illusion has always been part of show business.

* * *

Lea Michele has played Jewish characters before (in “Ragtime” as a kid, for example, and later on the popular TV series “Glee”). Did anyone object to her playing such characters? Of course not! She was a good actor. She made you believe she was whatever character she was playing. And that’s an actor’s job.

Valerie Harper—playing television’s Rhoda Morgenstern—was always convincing (and endearing) playing that enduringly popular Jewish character, first on “The Mary Tyler Moore Show” and then on “Rhoda.” I doubt most audience members knew (or would have cared one way or the other) that in real life Valerie Harper was not Jewish. She was certainly believable in her characterization. And that’s the most important issue. She was a wonderful actor, and played the role beautifully. That’s my two cents, anyway.

* * *

I recently revisited “Funny Girl.” And let me tell you, Lea Michele really does a sensational job. It’s not just the big bravura vocal numbers, like “Don’t Rain on My Parade,” that you know she can deliver. Her acting was fierce throughout, she was utterly committed. She held me; she made me feel almost like I was seeing this show–which I know so well–for the first time. She was equally convincing as young Fanny Brice, striving to get her first break, and as the more aware, disillusioned Fanny Brice we see by night’s end. Watching her fall in love with Nicky Arnstein, I bought every moment, as if I were eves-dropping on something happening right now.

I’ve watched Lea Michele perform since she was a kid. (I even attended the cast-album recording session, when she was the Little Girl in “Ragtime.”) But this is, by far, the best work she’s ever done. I did not know she had this in her. Should we have been deprived of this performance—an unforgettable star–turn, a near-perfect pairing of performer and material—because Michele does not identify as Jewish? To me, that would be absurd. She’s brilliant in “Funny Girl.” And I’m glad she was cast. She’s a much stronger Fanny Brice on stage than Beanie Feldstein was.

I might add that at the performance of “Funny Girl” that I caught recently, Stephen Mark Lukas sang and acted the role of Arnstein excellently. (He’s the understudy; I actually preferred him to the actor he was filling in for. Incidentally, he’s just been picked to play Arnstein in the upcoming national tour; audiences will definitely be getting their money’s worth).

Debra Cardona, going on as Fanny’s mother, was terrific, too; dry, funny, impactful. Terrific work. I was savoring every line delivery. I have no idea if Lukas or Cardona—understudies whom I just happened to catch recently, covering the roles of Nick Arnstein and of Fanny’s mother—identify as Jewish or not; nor would I find that information important. These were performers doing satisfying work. (And Jared Grimes, whom I loved when the show first opened, continues to shine playing Eddie Ryan, a fictitious character invented by Isobel Leonhart who wrote the original book for “Funny Girl.” And Grimes really connects with the audience.)

Side note: I still am saddened that this revival is notably smaller in scale (in terms of both cast–size and orchestra–size) than was the lavish original Broadway production, which I remember so fondly. It has a notably cheaper look and feel than the original. It’s not nearly as big and glamorous a production; and to me, that’s a pity. But I doubt there were many old-timers like me in the audiencewho were comparing what they were watching in 2023 to the original production from the 1960s. The audience theother night was clearly enjoying what they saw.

This revival of “Funny Girl” feels much more satisfying now than when it first opened last year—and that is thanks to the star-power of Lea Michele. She gives a far more effective and consistent performance than Beanie Feldstein gave. And she’s brought out the best in everyone around her. The audience, the night I attended recently, was enthusiastic throughout. At night’s end, everyone leavingthe theater looked like they’d had a great time. They’d seen a show with four strong performers heading the cast, and a great score. Plenty to enjoy!

One more side note. Personally, I think it‘s a shame that this production—which clearly is pleasing audiences–is scheduled to close on September 3rd. The production opened last year with a badly miscast actor in the lead, and her insecurity on stage weakened the whole productionback then. That created a negative buzz about the show. After a few months, the producers hired Lea Michele in to take over the starring role. It’s simply a much more rewarding show now than it was when this production opened last year. It’s been doing much better business at the box office, too. (The house appeared to be jam-packed, the night I attended.) I wish the producers could find a way to persuade Leas Michele to extend, so that the production could enjoy a longer run. Or find someone else—famous or unknown–(perhaps Leslie Kritzer? Shoshana Bean? Anna Kendrick? Ana Gasteyer? Farah Alvin? Dea Julien?)—who could take over the role. I saw Mimi Hines star in “Funny Girl” during its original Broadway run at the Winter Garden, right after Streisand left the production, and I hung on every word. Hines did the role her own way, and she kept audiences coming for many months. I enjoyed her performance tremendously.

“Fanny Brice”—as portrayed in “Funny Girl”—is a highlydemanding role. Not easy to cast. And I can’t predict who would sell enough tickets to sustain the production. But I’d like to believe there’s someone out there who, properly promoted, might be able to keep the current Broadway revival going. I hate seeing any production close. That glorious score in “Funny Girl” deserves to be heard. And the story of Fanny’s ill-fated love for Arnstein continues to hold us.

* * *

Friends in the business whom I respect continue to debate online whether only someone Jewish should be cast as Fanny Brice. Some are using the term “Jewface” if an actor who’s not Jewish is hired to play a Jewish character; they consider that a demeaning form of cultural appropriation. (They’re likening such casting of non-Jews as Jews to the old-time use of blackface makeup, in which whites performed as Blacks.) But I don’t think the issue is quite that simple.

Because if you start saying that only a Jew can a portray a Jew you’re on a slippery slope. Should a Jewish actor then be forbidden to play a Christian character? If you’re casting a production of “The Sound of Music,” would you only allow Christians (or Austrian Christians, for that matter) to play members of the Von Trapp family, since the real-life Von Trapps were Austrian Christians? That would be crazy.

Should Pearl Bailey, who was Black, have been forbidden to play Dolly Gallagher Levi (in the musical “Hello, Dolly!”), because the character was originally conceived and written as a white Irish-American widow? Bailey’s performance in that show—perhaps the high point of her illustrious career—was one of the greatest performances I’ve ever seen on Broadway.

And before people try to dictate who should play which roles, let’s not forget the Equal Employment Opportunity laws. It is illegal for a workplace to discriminate against an applicant or an employee on the basis of race, religion, sex, national origin, age or disability. The employer may only consider factors that are essential for fulfilling the requirements of the job.

A casting director’s first priority should be finding the actor who can best play a particular role. That may be an actor who shares the same heritage as the character being played; but it may not.

* * *

When I was developing my show “One Night with Fanny Brice” (which is published and licensed by Leicester Bay Theatricals), I saw lots of actors audition for the role of Fanny Brice. I tend to run leisurely auditions. I enjoy talking with actors, getting to know them a bit. I never asked anyone their religion. (I still do not know the religion of some fine actors who have wound up playing the role of Fanny Brice in one production or another.)

But occasionally, during auditions, actors volunteered the information that they identified as Jewish. Initially, I assumed that might make them better qualified to portray Brice—that they’d understand Brice’s world better because they had a shared heritage–but I soon discovered that wasn’t always the case.

One of the first women to audition for me told me that she’d grown up in an upscale suburb on the West Coast.She’d recently moved to New York. She described her family background as secular Jewish. She said her only knowledge of Brice came from having seen the movie “Funny Girl.” She’d never seen footage of Brice herself, nor had she heard any recordings of Brice. She sang well. She chose “People” as an audition number.

I handed her some pages of the script for “One Night with Fanny Brice” and asked her to read a bit. She glanced at the script and asked me what the words “kasha varnishkes”—which she had difficulty pronouncing—meant. I explained that “kasha varnishkes” was a meal, enjoyed by many Jewish families who’d emigrated (as Fanny’s had) from Eastern Europe. She’d never heard of it. We talked more. She did not know what latkes (potato pancakes) were. I asked her if she knew anyone—perhaps an older relative, a family friend, or someone in the business–who spoke Yiddish or spoke English with a Yiddish accent. She said no. I asked her if she knew any Yiddish words. She said she didn’t think so. I asked her if she could give me an oldtime New York Jewish accent. She said she wasn’t good with accents, generally, but she was diligent and would work hard to learn any accent that might be needed for any role she ever got a chance to play.

And I’m sure she would have worked hard. But she had no particular connection to Fanny’s world. She would have studied—like any good actor, of any background—to play the role as best she could. But the mere fact that she identified as Jewish did not necessarily ensure that she’d be able to play the character better than someone who was not Jewish. She was simply too far removed from Fanny’s world.

* * *

George Burns (1896-1996) told me that for decades he loved hanging out at Los Angeles’ famed Hillcrest Country Club because for him it was, in a sense, like going back to the old neighborhood where he’d grown up. He’d kibbitz with performers of his generation like the Marx Brothers, Eddie Cantor, George Jessel, and lesser-known old-timers because they all had so much in common. They’d all grown up as poor Jewish kids in turn-of-the-century New York City. They’d been raised by immigrant parents and grandparents who spoke Yiddish; the foods they enjoyed, the jokes they told, the way they phrased things speaking in English, or the way they’d inflect a line to make a point…. these were all part of a Yiddish culture that was vibrant in their youth. Fanny Brice came out of that same culture.

Talking with me, Burns could get nostalgic about the New York of his boyhood. He was then in his 90s, but he mentioned to me that on his last trip to New York, he’d stopped by Yonah Schmmel’s Bakery on the Lower East Side, which was still making knishes the way it had when he was a boy in that neighborhood and Yonah Schimmel himself ran the place.

In his 90s, George Burns was still going to Hillcrest Country Club regularly, but he’d outlived virtually everyone from his generation. And while he was treated with respect by the young comics there–treated like the American institution that he’d become–he missed being able to hang out with people who shared the same cultural references. The younger ones, he noted, didn’t understand the world he knew in his youth.

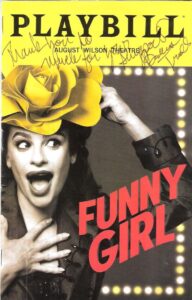

And so it is with young actors of today seeking to portray Fanny Brice or Nick Arnstein, or Fanny’s mother, Rose, or Rose’s friends and neighbors. That world is so distant from all young actors of today—of any religious or ethnic background—that they’re going to have to do some research. That world wasn’t quite so distant during the original Broadway run of “Funny Girl” in the 1960s; I was fascinated to read in my “Funny Girl” Playbill from back then (which I still have) that one of the older cast members had actually worked with Brice herself on Broadway, back in the 1920s. And there were still some old-timers around with the Yiddish accents that were so commonly heard in New York in Fanny’s youth.

I was surprised—although I shouldn’t have been—when actors auditioning for my Fanny Brice shows told me they didn’t know anyone who spoke Yiddish, or had a Yiddish accent. I’d explain to them that if they wanted to capture Brice, at times they’d have to be able to comfortably and naturally slip into a Yiddish accent, or give a line a Yiddish-flavored inflection. That was an intrinsic part of Brice. The actors would ask me to make them tapes of Brice from rare recordings in my collection, so they could get a better feel for her. I was glad to do so.

* * *

When I was developing my one-woman show “One Night with Fanny Brice,” one friend whom I especially hoped would like it—and I was so glad he did!—was Jack Gottlieb. Jack (1930-2011) was like family to me, a very special lifelong friend. When I was a little boy in New Rochelle, New York, the Gottliebs lived next door to us. We called Jack’s mother “Gramma Gottlieb.” I honestly thought she was my grandmother; that’s what we called her and we loved her; I was too little to understand that she was my “honorary” grandmother. I was in her house all the time.

She and her kids babysat me, but I didn’t think of it as babysitting; for me, it was just being with family. I began learning to cook—which I still love–in her kosher kitchen, helping her prepare whatever she was making, from lakes to chicken. (Latkes are still a favorite comfort food of mine.) She enjoyed going to the Yiddish theater. She spoke Yiddish sometimes, English–with–a–Yiddish–accent most of the time. And I loved that accent of hers (which you hardly ever hear anymore, because those Yiddish-speaking immigrants from Eastern Europe have passed on); I still associate it with her warm, loving voice. And when I heard, for the first time, Fanny Brice’s record, “Mrs. Cohen at the Beach,” with similar sorts of inflections, it was a voice that felt almost like family to me.

Grama Gottlieb’s children could speak Yiddish, too, although they almost always spoke English. If Jack—or “Jackie” as I always called him, just the way his mom did—took me to a Yiddish theater production, he could translate for me. I really thought we were all one family; I told my friends and my teacher in kindergarten that I was Jewish because I thought I was; so did my brother. Gramma Gottlieb talked about her faith; my parents didn’t. I was shocked when I was old enough to start going to Sunday School and I learned that I was supposed to be a Christian. What did I know about religion?

Jack was a wonderful pianist and composer, and knew seemingly everything about music and old-time show business. He became Leonard Bernstein’s assistant conductor, personal assistant, and intimate friend. (I was so proud when I got to see Bernstein conduct music that “my” Jackie Gottlieb had composed—to a kid that was a big deal.) It was Jack Gottlieb who saw that I had an interest in the performing arts—I was such a dramatic child–and suggested I take acting classes at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, which I loved. (I also enjoyed occasionally plunking out notes on his family’s piano, but I did not havehis gift for the piano. However, he saw and encouraged my interest in the performing arts. He provided my first point of entry into that world.)

Jack Gottlieb was passionate about Bernstein’s music (and Bernstein himself), and serious modern music. He loved the great vaudevillians, too, and knew everything about artists like Fanny Brice, Al Jolson, Eddie Cantor—all of whom I too loved. And he loved the creators of the Great American Songbook. In time, I came to share all of these loves. And throughout my life, I enjoyed going to shows with Jack. He was a wonderful mentor in lots of ways. And knew well—and communicated clearly—the richness of Yiddish culture.

Eventually Jack wrote an invaluable book, “Funny, It Doesn’t Sound Jewish: How Yiddish Songs And Synagogue Melodies Influenced Tin Pan Alley”—the definitive book on that subject. Nobody in the world understood the field better—Jack knew well the works of everyone from Fanny Brice to the Gershwins, to Jolson, to Harold Arlen, to Bernstein, and on. No one else could have written that book. (I was proud to have helped him a little bit with it, and get acknowledged in the book, just as I was proud to contribute photos from my collection to the definitive biography of Brice, “Fanny Brice: the Original Funny Girl,” written in 1992 by Herbert Goldman.) Jack and I were kindred spirits.

He followed developments in modern classical music. He composed concert pieces, theater works, operas, and sacred music; but he had big ears and never lost his love of the popular entertainers—like Brice—who had roots in Yiddish culture. It saddened him to see that Yiddish culture die out.

I remember one time we went to see a production of “Fiddler on the Roof”—a show he knew well and loved—at Bucks County Playhouse. He was disappointed because that particular production had very little ethnic character; he felt that a certain Jewish flavor, essential to “Fiddler on the Roof,” was missing. He told me: “I doubt that anyone involved in that production is Jewish. Or if any are from Jewish families, they’re not from observant ones. They didn’t even get the lighting of the candles right in the show; they don’t know the traditions.” He felt that if the producer, director and actors weren’t familiar with Orthodox Jewish customs, it was their responsibility to educate themselves, or to bring in someone to ensure that, at a minimum, Sabbath traditions were represented properly.

Jack didn’t believe that only Jewish actors could portray Jewish characters. But he wanted to see Jewish life represented accurately. I feel the same way.

* * *

I’d like it if whoever portrays Fanny Brice, Fanny’s mother, and family friends can evoke the world in which they lived. And offer, at times, the accents and inflections that were part of that world.

Some actors, preparing to play Fanny Brice in shows of mine (and I’ve written three different published shows about Brice: “One Night with Fanny Brice,” “The Fanny Brice Story,” and “Presenting Fanny Brice,”), found it helpful to listen to tapes I made for them of rare Brice performances from my own collection, including material that had never been released on any albums.

In the past year, growing more aware of my own mortality and wanting to share items from my Brice collection with a broader public, I’ve released three CDs that include Brice performances. These are now available as physical CDs from Amazon, Ebay, Footlight.com, and other sources, and in digital form from Amazon, Apple iTunes, and many other sources.

Anyone who wants to know a bit more about what the actual Fanny Brice sounded like may find these historic CDs valuable.

* * *

The first Brice CD I released is “Fanny Brice: the Real Funny Girl, Rare Performances Curated by Chip Deffaa.”

“Fanny Brice: the Real Funny Girl” is available from Amazon here: https://www.amazon.com/Fanny-Brice-Real-Funny-Girl/dp/B09T3BB9DP/ref=sr_1_1?crid=19S1MU2EAKPZ2&keywords=fanny+brice+the+real+funny+girl&qid=1689636701&s=music&sprefix=fanny+brice+the+real+funny+girl%2Cpopular%2C155&sr=1-1 )

This CD includes Brice interacting with the likes of Bob Hope, Jack Benny, Al Jolson, Talullah Bankhead. We hear her sing “My Man” slowly, expressively—the first hit torch song in America. And also offer “My Man” in a surprisingly brisk, jazzier version. (Neither of these versions have ever before been released on albums.)

“Soul Saving Sadie” and “Rose of Washington Square” are extremely rare “live” recordings of Brice performing them on stage in the mid-1930s in the Ziegfeld Follies—two of the earliest “live” theatrical recordings in existence. The audio quality is far from high fidelity, but their historic importance—we’re hearing this superstar “live” in performance in the theater–more than makes up for that.

On “Becky is Back in the Ballet,” she is a Jewish mother proudly watching her daughter’s ballet recital. On “Pocahantas,” she recreates on radio (introduced by Wallace Beery) a sketch she first did in the Ziegfeld Follies.

The next Brice CD I’ve produced is “Fanny Brice: Rare and Unreleased Recordings Curated and Introduced by Chip Deffaa.”

“Fanny Brice: Rare and Unreleased Recordings” is available from Amazon here: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0CBXMGSKD/ref=sr_1_1?crid=QAVPSLP4Z9UR&keywords=fanny+brice+rare+and+unreleased+recordings&qid=1689499594&s=music&sprefix=%2Cpopular%2C347&sr=1-1 )

This CD includes a wonderful rendition of one of Brice’s classic numbers, “I’d Rather Be Blue Over You”—a version available nowhere else. (In the current Broadway revival of “Funny Girl,” Lea Michele now sings a bit of that great Brice song—which was not included in the original Broadway production of “Funny Girl,” nor in this revival when it first opened last year. I wish it were longer; she sings it well.)

And we hear a rendition of Brice’s famous monologue, “Mrs. Cohen at the Beach”—which she performed, with variations, in vaudeville, in the recording studio, and on film. This was stand-up comedy, in a sense, before that term had been coined. She’s giving us a character portrait of a mother and her family at the beach, and the gentle humor emerges from the truthfulness of the portrait.

We hear her in classic “Baby Snooks” routines, exasperating her parents. And having fun on the air with Frank Morgan (best remembered as the Wizard in “The Wizard of Oz”). She plays a German-American woman and an Irish-American woman in one early sketch (“The Marriage Bureau”); the humor is dated, but the routine reminds us that she liked to play all different characters. And at one point in a 1916 recording, “If We Could Only Take the Word,” she gives us still another characterization—a gay clerk. In the delightful song “Cooking Breakfast for the One I Love,” she sings the first chorus straight, then slips into her Yiddish accent for the second chorus. She could—and did—drop in and out of that accent at will. It was part of who she was.

I’ve included several performances by Brice, along with rare performances by such contemporaries as Al Jolson, Eddie Cantor, George M. Cohan, Will Rogers, and Sophie Tucker on “Chip Deffaa’s Broadway and Vaudeville Legends.”

“Chip Deffaa’s Broadway and Vaudeville Legends” is available from Amazon here: https://www.amazon.com/Chip-Deffaas-Broadway-Vaudeville-Legends/dp/B0C3H4CPM9/ref=sr_1_1?crid=158EIBL7GXZPY&keywords=chip+deffaa%27s+broadway+and+vaudeville+legends&qid=1689636798&s=music&sprefix=chip+deffaa%27s+broadway+%2Cpopular%2C152&sr=1-1 ). And it provides a window onto the entertainment environment Brice was part of. Lots of good, rare performances by some of the biggest stars of the earliest 20th Century.

You can also buy all three CDs as a set, offered at a special price, benefitting the charity “Broadway Cares / Equity Fights AIDS,” “Fanny Brice & Friends: the Ultimate Collection.”

“Fanny Brice & Friends: the Ultimate Collection” isavailable from Ebay here:

https://www.ebay.com/itm/374814535502?hash=item5744afef4e:g:8O8AAOSwwvdksq8z&amdata=enc%3AAQAIAAAA4KTYe2SCnJ4lqRQZAj3HP8n5WZ8Wa0Swf%2B77HLz2%2FMblANb8XdjgCfXni3RUM2UB%2FQMWvGtuqhv%2B1MbYs2LU76Qph3oV3PrYbfFhvpAg9euTMYXSC9L90V6hN4Alu4VfshIlr8YrSJJX0rsDHYmg0oOxnQmPERomUiMbKY5xywJoy5iYd2MWXiuSl7jvSdM3piuZNrhp22c%2B5gqnXIDAA1TYQaDll9bs00fiVhCKm7eidZT8QitPGXdq%2Blw%2F%2Fbk4oX%2FLHmz19d6NvTDnkFmL4128ABI0S6TzTonAbfTdh99Y%7Ctkp%3ABFBM8qGq46xi )

Brice was a great artist. Much of her work was performed “live” in theaters, before audience members who have now passed on. I wish there were more of her work preserved on recordings or on film. (I listened to more than 150 Brice radio performances to select bits for inclusion on these CDs.) I’m glad to share what I can.

Gilbert Seldes—one of the most respected critics of his day—wrote in the 1920s that he knew of no other woman who could hold a theater audience the way Brice could. He said that her command over live audiences felt almost supernatural in its power.

Billy Rose—Brice’s third husband—noted that although his marriage to Brice ended acrimoniously, his admiration for her tremendous gifts as an artist never wavered. When “Funny Girl” was set to open on Broadway, he said he had no interest in seeing it. He’d never seen a greater female performer than Brice on stage—to him Brice was “thunder on the mountains”—and he didn’t believe anyone could do her justice.

I’m glad Brice is currently being represented on Broadway by as potent a performer as Lea Michele. I’ll be sorry to see her run come to an end on September 3rd. But I hope some writers create good new shows for her. She has a lot to offer. And the theater needs her. I also wish her performance as Fanny Brice could be preserved in a film or TV adaptation.

I’m looking forward to seeing Katerina McCrimmon play this iconic theater role in the forthcoming national tour. She has some big shoes to fill.

Break legs!

It’s not an issue of Jewish performers “owning” Jewish roles, but they should certainly have the chance to perform characters of their own people, as artistic expression. As for characterizations, there are nuances that 90% of non-Jews will not convey. Jews are not just another ethnic group. Why should a Jewish actor only get to play Italians? Italian actors get to play Italians and Jews, like John Turturro. The fact is, typical “non-traditional” casting erases the meanings and contexts of characters, while only black people ever play “black” roles. So, stop the hypocrisy. Fanny Brice is a Jewish icon and all preference should be given to Jewish actresses. Mimi Hines, if not Jewish, though she may be, is exceptional.